Imam Hasan Taim had already been shot twice before the camera started recording.

On July 20, 2024, Taim was in Jatrabari, a neighbourhood in Bangladesh’s capital city Dhaka, when the police started firing.

He was one of the student protesters in a crowd that had gathered to demand the resignation of the now-ousted prime minister Sheikh Hasina.

In the now-viral footage, taken by a journalist called Arefin Mahmud Shakil, Taim is seen being dragged by his friend Rahat Hossain to safety.

A few seconds in, a police officer is seen shooting Taim at close range. The officer’s name was later identified as Jakir Hossain.

Rahat was also injured but he continued to drag Taim. In the next few seconds, Jakir was seen shooting Taim again, then again.

Unable to go on any further, Rahat fled to save his own life.

Ironically the son of a police officer himself, Taim was left at the scene for half an hour before officers carried his body to Jatrabari police station. There, his family claims that the officers trampled their son – who was alive until then – to death.

“My brother would have survived had he been taken to the hospital,” said Rabiul Awal, Taim’s older brother, to Asian Dispatch. “But after they took him to Jatrabari thana (police station), a group of officers led by an officer called Assistant Commissioner (AC) Nahid Ferdous trampled him to death.”

Taim’s family identified at least eight more police officers from the Dhaka Metropolitan Police alongside Jakir, including Additional Deputy Commissioners Shakil Mohammad Shamim and Shahadat Ali, and Additional Deputy Commissioner Masudur Rahman.

Taim’s brother Awal told this reporter – based on his review of government documents – that out of this group of cops, Nahid Ferdous was later transferred and stationed at a Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) camp in Jhinaidaha district, which is nearly 200km from Dhaka. RAB is a paramilitary force in Bangladesh sanctioned by the US for human rights abuses under Hasina’s rule.

Taim’s family filed a case against 10 police officers, including Jakir, Iqbal Hossain, Shakil, Tanjil Ahmed, Shahadat, Masudur, Nahid, Shudipta Kumar, and Wahidul Haque, in a Dhaka court. Among them, only Abul Hasan, Tanjil, and Shahadat have been arrested.

The family also filed a case against the accused at the country’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), where warrants were issued for several officers, including Nahid.

“The ICT issued warrants for them on Nov 12. But Nahid was on duty until Nov 20. How is that possible?” Tuhin asked, implying Nahid’s connection with an influential Dhaka Metropolitan Police official. He suspects forces within the police are sheltering the accused officers.

Disproportionate police violence

The mass uprising in Bangladesh - South Asia’s youngest country formed in 1971 - was a pivotal moment in the world that saw thousands of people, mostly students, not only shake Hasina’s 16 years of autocratic rule but dismantle it entirely.

Hasina fled the country - she’s in hiding in India - but left, in the wake of her ouster, a lasting legacy of police brutality.

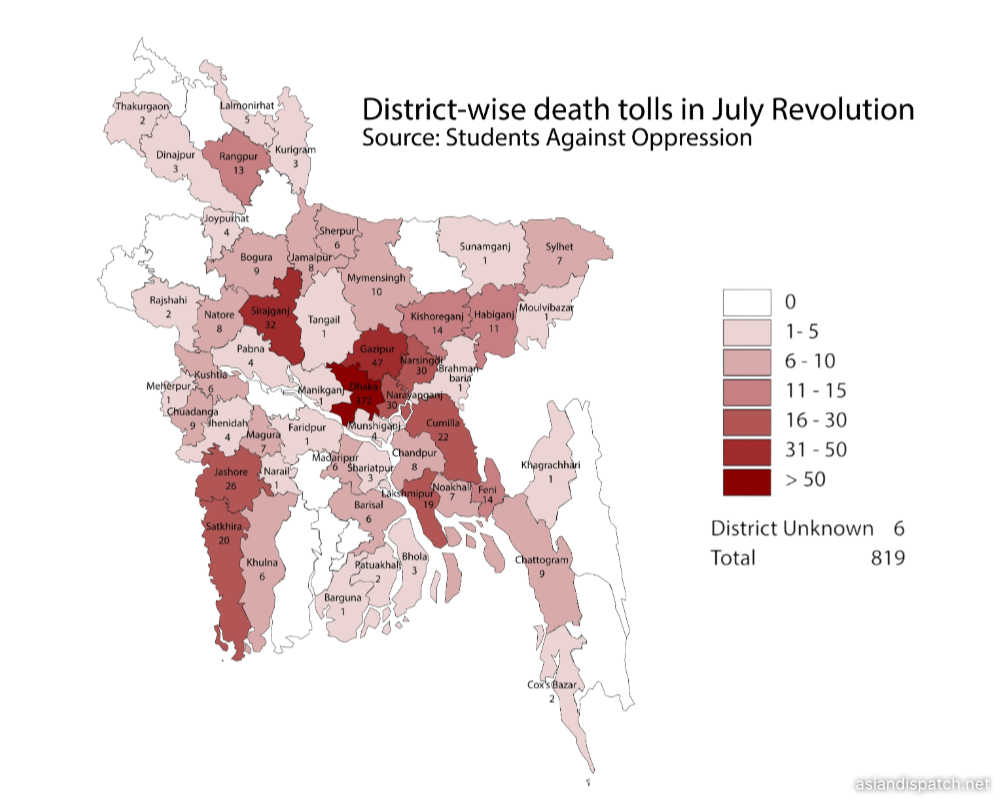

From July 16 to Aug 5, 2024, more than 800 people, including at least 89 children, were killed by the police, other security forces, and men associated with Hasina’s party.

On July 19 alone – the day the fallen regime enforced an internet blackout – at least 148 people were killed by law enforcement agencies, according to a report by the International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP) and Tech Global Institute.

“Shockingly, 54 of the dead were shot in the head or throat. Many of those killed were not even part of the protests, but bystanders and people who happened to live or work close to the shooting that was completely indiscriminate,” the ITJP report found.

Among them were children as young as four-year-old Abdul Ahad and six-year-old Riya Gope, each shot in the head in front of their parents at home during an attack on protesters in their neighbourhood.

In a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), released on Jan 27, 2025, a police officer was quoted as saying, “I witnessed officers firing at vital organs…. In many cases, I witnessed live ammunition being fired even when officers’ lives were not in danger.”

Another police official described, to HRW, how senior officers in the Dhaka Metropolitan Police headquarters watched live CCTV footage and directed officers on the ground to shoot protesters as if “they were ordering someone to shoot in a video game.”

Many of the July-August killings were captured on video by bystanders and journalists.

Law enforcement agencies shot citizens from helicopters, killed children in their homes through windows, targeted long-range shooting aimed at protesters, denied treatment, and burned bodies after killing people.

After Hasina fled the country, legal cases against cops poured in from families of the deceased.

Top officers, including the then-inspector general of police Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun, Harun Or Rashid, Monirul Islam, and Biplob Kumar Sarker, face dozens of murder charges each.

According to a list of cases against police officials obtained by Asian Dispatch, at least 94 officers face charges of murder or torture.

Different reports published in local dailies such as Prothom Alo also suggest nearly a hundred police officers being charged. These statistics are now several months old.

Asian Dispatch reached out to various authorities – including Bangladesh’s police headquarters, CID, and International Crimes Tribunals – to confirm the estimated number of police officers facing murder charges. None of them provided answers.

“We don’t have information about this,” said Assistant Inspector General Enamul Haque Sagar, the police headquarters spokesperson, to Asian Dispatch. However, he did confirm that only 34 officers – as of Feb 5 – have been arrested so far in connection to the July uprising.

READ MORE: As a ‘Gen Z’ journalist, this is how I felt witnessing young Bangladeshis overthrow Sheikh Hasina

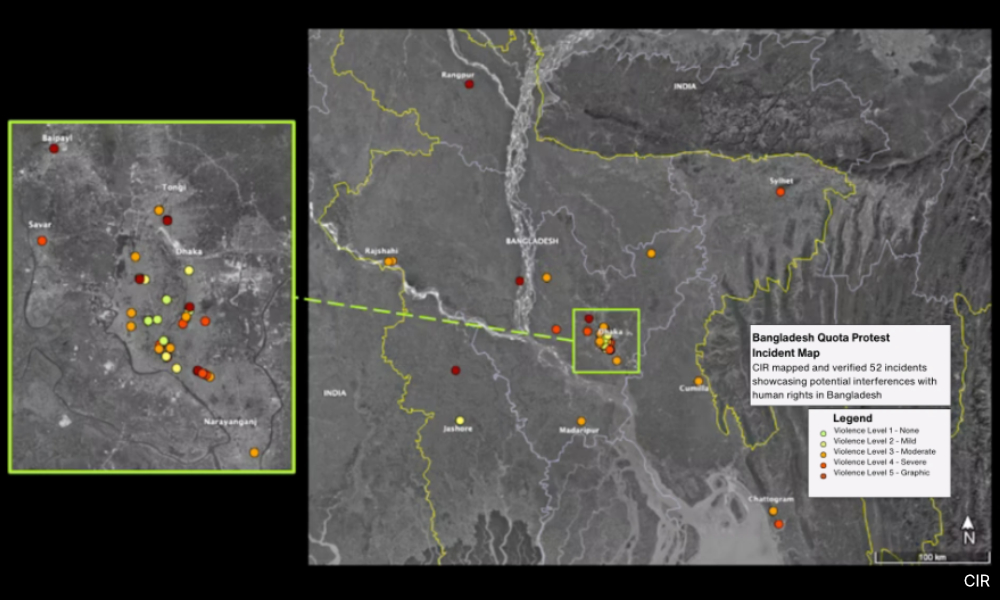

The Center for Information Resilience (CIR), an international agency that uses open source and digital investigations to expose human rights violations, verified 83 pieces of footage showcasing 52 separate incidents of police brutality in July-August. Of these, 24 showed verified casualties.

The CIR findings also identified “two peaks” in violence. The first was on July 18, when killings amounted to a massacre.

It all started with the killing of a protester called Abu Sayeed, in Rangpur district, on July 16, which was captured in a now iconic image of him spreading his hands in front of the police force.

The second “peak” in violence was on Aug 5, the day Hasina resigned and fled to India.

“Within these verified incidents, CIR identified a concerning trend of disproportionate violence by police officers and military personnel, which potentially breaches human rights, including the use of live ammunition against protesters, the desecration of bodies, and the beating of unarmed civilians,” the report states.

Cold-blooded targeted killing

On Aug 5, Mohammed Sujon Hossain, a police officer from the Armed Police Battalion (APBn), a specialised combat unit of the Bangladesh police, was seen shooting a protester.

On duty in Dhaka’s Changkharpur area, the official was seen firing a Type 56 semi-automatic carbine – an assault rifle often used by military personnel or armed groups – at protesters located less than 100m away.

In a video that was later aired on Jamuna TV, the official is seen shooting one protester, after which other officers join in. Sujon Hossain is seen leaning on his knee to shoot again and saying, “Someone is dead,” as other officers start shooting at unarmed civilians.

Sujon was arrested on Sept 12, 2024.

Asian Dispatch got the said footage verified by CIR. The video was shot from Zahir Raihan Road near the Sheikh Hasina National Institute of Burn & Plastic Surgery and Chankharpul General Hospital in the Chankharpul area of Dhaka, geolocated at 23.7238, 90.4010.

On this day, more than 10 dead bodies were reportedly brought to Dhaka Medical College Hospital from Chankharpul soon after the shootouts.

One of those shot dead was Shahriar Khan Anas, a 16-year-old student at Gandaria Ideal High School in Dhaka.

Before joining the march to Hasina’s residence, Anas wrote a letter to his mother saying, “Rather than staying at home like a coward, it is much better to join the struggle and be shot dead like a hero.”

His father, Shahria Khan Palash, filed a case at the ICT, naming Hasina as the prime accused, along with several police officers.

He told Asian Dispatch that he asked ICT to include the then-additional deputy police commissioner (ADPC) Akhtarul Islam in his case.

“Whenever I call, they [ICT] say my case is still being processed. But arrest is far away,” Palash said.

When contacted, ICT investigating officer Munirul Islam told Asian Dispatch they were still investigating the allegations and refused to share any details about charges, including the allegations against Akhtarul Islam.

According to the Bangladeshi Daily, The Business Standard, ADPC Akhtarul Islam was seen in command in Chankharpul that day.

Another police officer present there told The Business Standard that, “Sir Akhtarul himself also fired that day.”

When Asian Dispatch asked ICT about Akhtarul Islam’s whereabouts on the aforementioned day, spokesperson Enamul Haque Sagar responded: “We don’t have that information.”

In another part of Dhaka, another police officer called Arafatul Islam was seen in a video near a van where police officers were loading several dead bodies, with at least six other officers in the background.

The bodies were later burned on a truck. Arafatul was subsequently arrested for concealing evidence of police brutality.

Md Abdullahil Kafi, the additional superintendent of police (crime and operations) in Dhaka, was also arrested in connection to this case.

Escaping justice

Asian Dispatch reviewed around 100 videos from this time and corroborated those of over a dozen police officers in connection to the July-August violence.

The interim government of Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus has, so far, set up a foundation to support the families of wounded and killed, with a funding of 1 billion Bangladeshi Taka (RM35.9 million).

In January 2025, the Police Reform Commission submitted recommendations to curb abuse of power and excessive force by the police. But mounting evidence shows little to no attempts to bring the accused to justice.

Another accused official, Harun, the then additional commissioner (Crime and Operations) of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police and former chief of the Detective Branch, was rumoured to have been detained after Hasina fled.

Rashid dismissed those claims in a text message to the Daily Star on Aug 6.

However, despite a travel ban on him by a Dhaka court on Aug 27, Rashid appeared in an interview with a US-based Bangladeshi journalist in October, where he denied all charges.

He continues to be at large. Asian Dispatch couldn’t confirm his whereabouts to secure an interview.

Former head of the police’s Special Branch (SB), Monirul Islam, who faces several cases too, also remains free. Asian Dispatch found him active on social media – his last post on his Facebook account was Jan 21.

Asian Dispatch contacted him via WhatsApp but did not receive a response at the time of publishing this story.

Many other top police officers are believed to have fled Bangladesh after Aug 5.

Salahuddin Miah, the former officer in-charge of Khilgaon police station in Dhaka during the protests, faces charges but is currently stationed in Rangamati with the Armed Police Battalion.

“The cases against me are related to BNP programs from [2023], not the July uprising,” Salahuddin told Asian Dispatch, referring to police violence against a Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) rally in 2023.

Attempts to reach out to up to 15 police officers facing charges of murder and torture were in vain. Their whereabouts remain unknown and they did not respond to messages and calls.

Government’s efforts and limitations

On July 20, when Moynal Hossain discovered the lifeless body of his son, Taim – the young protester mentioned at the beginning of this report – riddled with bullets, he called his superior in despair, crying, “How many bullets are necessary to kill a person?”

Moynal is a senior sub-inspector from the Bangladesh police.

Despite his rank and evidence, the grieving family claims they were denied the right to file a case.

Ramizul Huq, the investigating officer from the Police Bureau of Investigation assigned to Taim’s case, told Asian Dispatch that arresting government officers requires authorisation from the relevant authorities.

For instance, arresting an assistant superintendent of police or higher ranks requires permission from the Home Ministry, while constables to inspectors need approval from the Inspector General of Police.

“At the same time, multiple investigating officers were being changed, which caused further delays. Sometimes, following these procedures takes considerable time,” said Huq.

Taim’s family is among many waiting in darkness for justice. Many live in fear of consequences from the charges they’ve pressed against police officers since the accused remain free.

“We are scared to talk to the press. If they find out I am speaking against them, I fear we may not be able to sleep peacefully in our own homes”, said Kamal Hawlader, whose son was killed in July, told Asian Dispatch.

Enamul, the police headquarters spokesperson, says the charges are being investigated with “great seriousness.”

“The investigations are ongoing, and the process of bringing those found involved to justice is in progress,” he added.

But these words of reassurance aren’t enough.

Human rights activist Rezaur Rahman Lenin told Asian Dispatch that internal processes and weak systems set by the government allow police officials to evade accountability.

“The government faces multiple challenges on various fronts, which they are unable to address due to a lack of commitment, prudence, and bureaucratic transformation,” he said.

Institutional fragmentations among different commissions and the International Crimes Tribunal are both visible and vibrant, he says.

“Harmonising legal approaches transparently and effectively is essential to ensure justice,” said Lenin, noting the paradox of relying on the same force accused of killing protesters in order to maintain law and order.

CR Abrar, the president of the human rights organisation Odhikar, shared similar concerns.

“It is deeply disconcerting that after such heinous crimes, only 34 are apprehended,” he said.

“The evil force protecting the accused officials remains dominant and continues to call the shots.”

This article was first published by Asian Dispatch, a network of Asian news organisations. It was edited by Pallavi Pundir.