SPECIAL REPORT | Analysis of leaked documents shows systems meant to prevent money laundering are defenceless against perpetrators.

Money laundering isn't a victimless crime. The free flow of dirty cash helps sustain criminal gangs and destabilise nations. And it is a driver of global economic inequality.

Laundered funds are often shunted between accounts owned by obscure shell companies registered in secretive offshore tax havens, allowing elites to hide massive sums from law enforcement and tax authorities.

An International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) analysis found that banks in the FinCEN Files regularly processed transactions for companies registered in so-called secrecy jurisdictions and did so without knowing the ultimate owner of the account.

Corporate account holders often provided addresses in the UK, the US, Cyprus, Hong Kong, the United Arab Emirates, Russia and Switzerland. At least 20 percent of the reports contained a client with an address in one of the world's top offshore financial havens, the British Virgin Islands.

The FinCEN Files is an investigative project by about 400 journalists worldwide spearheaded by ICIJ, involving "suspicious activity reports" (SARs) filed by the banks leaked to BuzzFeed News.

The banks file the SARs to the US Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which collects and analyses financial transaction information to combat money laundering and other financial crimes.

ICIJ's analysis found that in half of the reports, banks didn't have information about one or more entities behind the transactions.

READ MORE: US banks didn't act on 'suspicious' Jho Low, 1MDB-linked transfers until too late, leak shows

In more than 680 reports in the FinCEN Files, financial institutions asked for more information about entities, and on more than 160 occasions, other banks didn't respond. Some banks or branches in countries such as Switzerland cited local secrecy laws in their jurisdictions to deny the information.

Estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime indicate that US$2.4 trillion in illicit funds are laundered each year - the equivalent of nearly 2.7 percent of all goods and services produced annually in the world. But the agency estimates that authorities detect less than one percent of the world's dirty money.

"Everyone is doing badly," David Lewis, executive secretary of the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force, a partnership of governments around the world that sets anti-money laundering standards, acknowledged in an interview with ICIJ.

His organisation's country-evaluation reports - which dig into how well banks and government agencies meet anti-money-laundering laws and regulations - show lots of box-checking but little practical progress. Many countries seem more concerned with looking good on paper than actually cracking down on money laundering, he said.

Even an association of the world's biggest banks complained last year that regulators focus on "technical compliance" rather than on whether systems "are really making a difference in the fight against financial crime."

A bombing in Jerusalem

For some financial institutions, the problem client is another bank.

One early morning in 2003, Steven Averbach was on the Number 6 bus in Jerusalem, when a man rushed to board as the bus pulled away.

"There were too many things out of place" with the man, recalled Averbach, who grew up in New Jersey but immigrated to Israel as a teenager. The man wore long black pants, a white shirt and a black jacket, the typical garb of an Orthodox Jew. But he wore "tipped shoes" that didn't fit with the Orthodox sect dress, and his jacket was bulging.

In his right hand was a device that looked like a doorbell.

Averbach, who had previously served as the chief weapons instructor for the Jerusalem police force, drew his sidearm. But as the ex-cop turned to face the man, "he detonated himself", Averbach later testified in a video deposition.

The blast killed seven and wounded 20 others, leaving Averbach paralysed from the neck down. He died in 2010 of complications from the long-term effects of his injuries.

By then, he and his family had become plaintiffs in a lawsuit in the US accusing a Jordanian financial institution, Arab Bank, of moving funds that helped bankroll terrorists involved in the bus bombing and other attacks.

The FinCEN Files show that as the litigation was casting a shadow over Arab Bank, it was benefiting from a working relationship with a much bigger, more influential bank: Standard Chartered.

This UK-headquartered bank helped Arab Bank clients access the US financial system after regulators found deficiencies in Arab Bank's money-laundering controls in 2005 and forced it to curtail its money-transfer activities in the US

Standard Chartered continued its relationship with Arab Bank as the lawsuit against the Jordanian bank worked its way through US courts and even after American authorities put Standard Chartered on notice that it must stop processing transactions for suspect clients.

New York regulators concluded in 2012 that Standard Chartered had "schemed with the government of Iran" for nearly a decade to push through US$250 billion in secret transactions. The bank reaped "hundreds of millions of dollars in fees" and left "the US financial system vulnerable to terrorists, weapons dealers, drug kingpins and corrupt regimes".

This pattern of conduct cost Standard Chartered nearly US$670 million in penalties in the second half of 2012 as part of two deferred prosecution agreements and other deals with New York and US authorities.

Despite its official pledges to stay away from suspect customers, Standard Chartered processed 2,055 transactions totalling more than US$24 million for Arab Bank customers between September 2013 and September 2014, the FinCEN Files show.

Then, in late September 2014, Standard Chartered found another reason to back away from Arab Bank. In the lawsuit stemming from the 2003 Jerusalem bus bombing and other attacks, a jury in Brooklyn found Arab Bank liable for knowingly supporting terrorism by transmitting money disguised as charitable donations for the benefit of Hamas, the Palestinian militant group that the US classifies as a terrorist organisation.

More than a year later, compliance staffers at Standard Chartered sent FinCEN a suspicious activity report acknowledging the bank's dealings with Arab Bank up to a few days after the verdict in Brooklyn and expressing concerns about "potential terrorist financing".

But that wasn't the end of it.

Standard Chartered shifted nearly US$12 million more in transactions for Arab Bank customers from just after the verdict until February 2016, according to a follow-up suspicious activity report included in the FinCEN Files. Many wires referred to "charities", "donations", "support" or "gifts", the bank said.

The follow-up report noted that the payment records raised concerns - as in the Brooklyn trial - that "illicit activities" were being potentially funded "under the guise of charity".

The civil verdict against Arab Bank was overturned when an appeals court found flaws in the trial judge's jury instructions. Arab Bank then settled with nearly 600 victims and victims' relatives for an undisclosed amount.

In a statement, Arab Bank told ICIJ it "abhors terrorism and does not support or encourage terrorist activities". The bank said that allegations against it date back nearly 20 years to a time when anti-money-laundering laws, tools and technologies were different than they are now.

"In every country where it operates, Arab Bank is in good standing with government regulators and complies with anti-terrorism and money laundering laws," the bank said. The 2005 US regulatory limits against the bank were formally lifted in 2018.

Standard Chartered told the BBC, a partner of ICIJ, that it "initiated account closure" in connection to Arab Bank shortly after the jury verdict. "This process can take time in some cases," the bank said. "But in all cases, the bank continues to fulfil its regulatory obligations" while exiting accounts.

Arab Bank noted it "enjoys a longstanding relationship with Standard Chartered" that "continues today".

Standard Chartered no longer processes US dollar transactions for Arab Bank, but it still provides other banking services for the Jordanian financial institution, Arab Bank told ICIJ.

Rewards and risks

Why do banks move suspect money? Because it's profitable.

Banks can pad their bottom lines with the fees they collect as money spins through the webs of accounts often maintained by corrupt users of the financial system. JPMorgan, for example, scored an estimated half a billion dollars in revenue by serving as the chief banker to Bernie Madoff, according to filings in the bankruptcy case spawned by the collapse of Madoff's multi-billion-dollar Ponzi scheme.

Dealing with shady customers does carry risks.

JPMorgan paid US$88.3 million in 2011 to settle regulators' claims that it had violated economic sanctions against Iran and other countries under US embargoes. Treasury officials hit the bank with a "cease and desist" order in 2013 that described "systemic deficiencies" in its anti-money-laundering efforts, noting the bank had "failed to identify significant volumes of suspicious activity".

Then, in January 2014, the bank paid US$2.6 billion to US agencies to settle investigations over its role in Madoff's scheme. JPMorgan posted profits of more than double that amount in just that quarter on its way to nearly US$22 billion in profits for the year. Madoff pleaded guilty and is serving a 150-year jail sentence in federal prison.

JPMorgan continued, after those enforcement actions, to move money for people involved in alleged financial crimes, the FinCEN Files show.

Among them: Jho Low, a financier accused by authorities in multiple countries of being the mastermind behind the embezzlement of more than US$4.5 billion from a Malaysian economic development fund, called 1Malaysia Development Berhad or 1MDB. He moved just over US$1.2 billion through JPMorgan from 2013 to 2016, the records show.

Low first gained notoriety for partying with Paris Hilton, Leonardo DiCaprio and other celebrities. One night at a club on the French Riviera, he got into a bidding war over a cache of Cristal champagne - winning the contest with a final bid of two million euros, according to Billion Dollar Whale, a bestselling book about the 1MDB swindle.

He was first named by media reports in early 2015 as a key figure in the 1MDB scandal, the so-called "heist of the century". Singapore issued a warrant for his arrest in April 2016. Authorities in the US, Malaysia and Singapore are seeking his capture.

JPMorgan also moved money for companies and people tied to corruption scandals in Venezuela that have helped create one of the world's worst humanitarian crises. One in three Venezuelans is not getting enough to eat, the UN reported this year, and millions have fled the country.

One of the Venezuelans who got help from JPMorgan was Alejandro "Piojo" Isturiz, a former government official who has been charged by US authorities as a player in an international money laundering scheme.

Prosecutors allege that between 2011 and 2013, Isturiz and others solicited bribes to rig government energy contracts. The bank moved more than US$63 million for companies linked to Isturiz and the money laundering scheme between 2012 and 2016, the FinCEN Files show.

Isturiz could not be reached for comment.

The secret records show that JPMorgan also provided banking services to Derwick Associates, an energy firm that won billions of dollars in no-bid contracts to repair Venezuela's failing electricity grid.

A 2018 analysis by the Venezuelan chapter of the non-profit group Transparency International concluded that Derwick Associates failed to deliver the power capacity expected - and overbilled the Venezuelan government by at least US$2.9 billion.

Alejandro Betancourt was in his 20s when he co-founded Derwick with a younger cousin.

News articles and Internet postings from 2011 raised allegations about Derwick. The company later filed a lawsuit that claimed it was the victim of a smear campaign that falsely accused it of being part of a "criminal group". The suit was settled on undisclosed terms.

The FinCEN Files show that Derwick used accounts at JPMorgan to move at least US$2.1 million in 2011 and 2012 and that the bank processed other transactions of undisclosed amounts for Derwick and its managers at least into 2013.

In 2018, the US Justice Department charged a senior Derwick executive, Francisco Convit Guruceaga, in an alleged US$1.2 billion bribery and money-laundering scheme. Betancourt was cited in the criminal complaint as an unnamed co-conspirator, ICIJ partner Miami Herald later reported.

A lawyer for Betancourt said: "My client denies any wrongdoing." Convit's attorney declined to comment.

In a general statement, JPMorgan noted that it had acknowledged in 2014 that it needed to improve its anti-money-laundering controls and that since then it has invested heavily toward this effort.

"Today, thousands of employees and hundreds of millions of dollars are devoted to helping support law enforcement and national security efforts," the bank said.

'Boss of Bosses'

Often, the secret files show, banks handling cross-border transactions have little idea who they're dealing with - even when they're shifting hundreds of millions of dollars.

Take the case of a mysterious shell company called ABSI Enterprises. ABSI sent and received more than US$1 billion in transactions through JPMorgan between January 2010 and July 2015, the FinCEN Files show.

This amount included transactions through a direct bank account with JPMorgan, which ABSI closed in 2013, and through so-called correspondent banking arrangements, in which a bank with significant US operations, such as JPMorgan, allows foreign banks to process US dollar transactions through its own accounts.

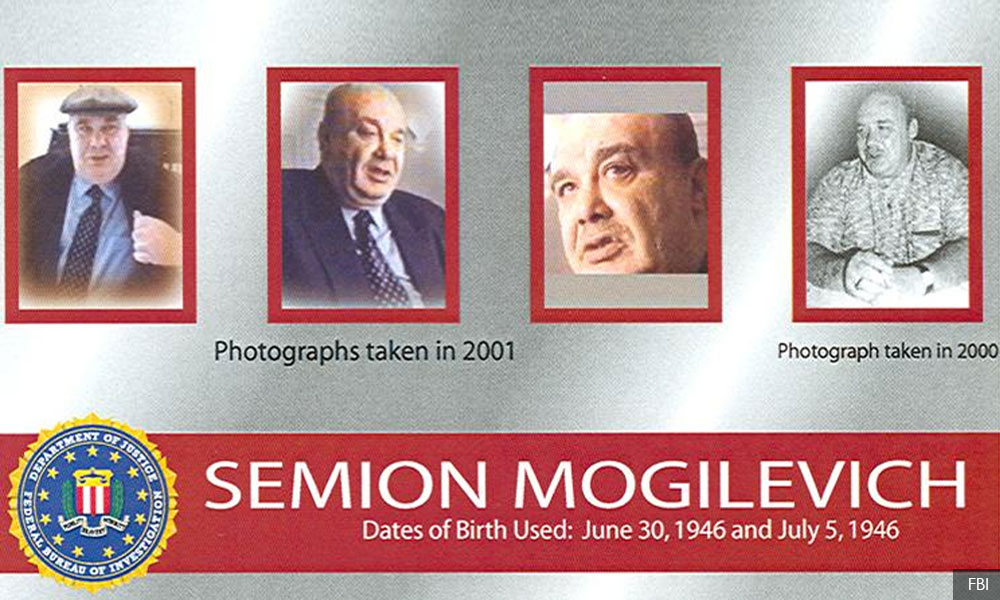

Compliance watchdogs based at the bank's Columbus, Ohio, operations hub decided to try to figure out ABSI's actual owner in 2015 after a Russian news site reported that a similarly-named shell company - which JPMorgan's records indicated was the parent of ABSI - was linked to an underworld figure named Semion Mogilevich.

Mogilevich has been described as the "Boss of Bosses" of Russian mafia groups. When the FBI put him on its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2009, it said his criminal network was involved in weapons and drug trafficking, extortion and contract murders. The chain-smoking, beefy Ukrainian's signature method of neutralising an enemy, The Guardian once reported, is the car bomb.

The records show the compliance officers searched in vain through their files on the shell company, unable to determine who was behind the firm or what its true purpose was.

While those details still remain unclear, JPMorgan had plenty of reasons to examine ABSI years earlier: it operated as a shell company in Cyprus, considered a major money-laundering centre at the time, and it was directing hundreds of millions of dollars through JPMorgan.

Mogilevich is featured in "World's Most Wanted", a Netflix documentary series released in August.

Through a spokesperson, Mogilevich said he had no knowledge of ABSI.

He has previously said: "I am not a leader or an active participant of any criminal group."

The Mighty Dollar

BuzzFeed News used the cache of suspicious activity reports in 2018 to publish stories revealing secret payments to shell companies controlled by Manafort, who is now serving a federal prison sentence in home confinement in a case based largely on these transactions.

A former US Treasury Department official, Natalie Mayflower Sours Edwards, has been charged with conspiring to unlawfully disclose FinCEN documents to BuzzFeed News.

BuzzFeed News has not commented on its source.

FinCEN and other US agencies play an outsized role in anti-money-laundering efforts around the world, largely because money launderers and other criminals share the same goal as many bank customers who operate across borders: turning their money into US dollars, the de facto global currency.

An elite group of mostly US and European banks with large operations in New York pocket fees performing this trick, drawing on their privileged access to the US Federal Reserve. Going through these banks' US operations is also the only way to move funds, already in dollars, between account holders in different countries.

American law entrusts banks with frontline responsibility to prevent money laundering, even though their financial incentives run entirely in the direction of keeping money - dirty or clean - moving. While banks are empowered to stop a transaction if it appears to be shady, they're not necessarily required to do so. They simply have to file a suspicious activity report with FinCEN.

FinCEN, which has roughly 270 employees, collects and sifts through more than two million new suspicious activity reports each year from banks and other financial firms. It shares information with US law enforcement agencies and with financial intelligence units in other countries.

Long gone

Inside big banks, systems for sniffing out illicit cash flows rely on overworked, under-resourced staffers, who typically work in back offices far from headquarters and have little clout within their organisations.

Documents in the FinCEN Files show compliance workers at major banks often resort to basic Google searches to try to learn who's behind transfers involving hundreds of millions of dollars.

As a result, the secret documents show, banks frequently file suspicious activity reports only after a transaction or customer becomes the subject of a negative news article or a government inquiry - usually after the money is long gone.

In interviews with ICIJ and BuzzFeed, more than a dozen former compliance officers at HSBC called into question the effectiveness of the bank's anti-money-laundering programmes.

Some said the bank didn't give them enough to do beyond cursory looks at large flows of cash - and that when they requested information about who was behind big transactions, HSBC branches outside the US often ignored them.

"They would say: 'Sure, we'll get back to you.' But they'd never get back," recalls Alexis Grullon, who monitored suspicious international activity for HSBC in New York from 2012 to 2014.

At Standard Chartered Bank, a lawsuit filed in December 2019 in the federal court in New York states that employees who objected to illegal transactions weren't ignored - they were threatened, harassed and fired.

Julian Knight and Anshuman Chandra claimed in the suit that they were forced out of management jobs at the bank after it learned they had cooperated with an FBI probe into transfers of money that Standard Chartered had pushed through for US-sanctioned entities from Iran, Libya, Sudan and Myanmar.

Standard Chartered, the suit claimed, engaged in a "highly sophisticated money-laundering scheme", altering the names of parties subject to US sanctions on transaction documents and creating a technological workaround that allowed illegal transactions to slip through the US Federal Reserve Bank undetected.

Chandra, who worked in the bank's Dubai branch from 2011 to 2016, concluded that the sanctions-busting helped bankroll terror attacks "that killed and wounded soldiers serving in the US-led coalition, as well as many innocent civilians".

The suit says the scheme allowed the bank to profit from the "high premium" that Iran and its operatives were willing to pay to convert Iranian rials - the country's sanctions-depressed currency - into dollars.

"You can run a show like this probably for a few months without being caught if it's a small group running it within the bank," Chandra said in an interview with ICIJ partner BuzzFeed News.

"But something like this happening over a period of years and coming into billions of dollars - someone at the top should have asked the question: How are we making this money?"

Chandra and Knight claim that the bank acknowledged only a fraction of its violations and lied about when illegal transactions had stopped when it came forward and admitted sanctions violations as part of its 2012 deferred prosecution deal with US authorities.

The agency extended the bank's probationary period again and again over several years. Then, in 2019, the bank paid US$1.1 billion more for continuing violations of sanctions against Iran and other countries and agreed to extend its deferred prosecution pact for two more years.

Standard Chartered didn't answer questions from ICIJ and its partners about the ex-employees' claims. In court papers, Standard Chartered said their allegations are implausible and meritless.

Yesterday:

US banks didn't act on 'suspicious' Jho Low, 1MDB-linked transfers until too late, leak shows

Secret docs show banks defy US crackdowns to serve oligarchs, criminals and terrorists

Unchecked by global banks, dirty cash destroys dreams and lives

Tomorrow:

'Tricks and cunning': Big penalties don’t stop banks from moving dirty cash

The Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is an independent international network of more than 200 investigative journalists and 100 media organisations in over 70 countries.