COMMENT | Lately, the call to close down vernacular schools as the way to foster national unity has gained traction again. In the most recent survey commissioned by Malaysiakini, the majority of non-Bumiputera respondents were reported to be against having single-stream education, while 58 percent of Bumiputera supported the move. Sixty-six percent among those who supported single-stream education believed that it is ‘key to unity of all races.’

This divisive issue has been a subject of recurring debate in Malaysia, and there are those who believe that a single-stream schooling system could really foster national unity. The question - is there empirical evidence to support such a position?

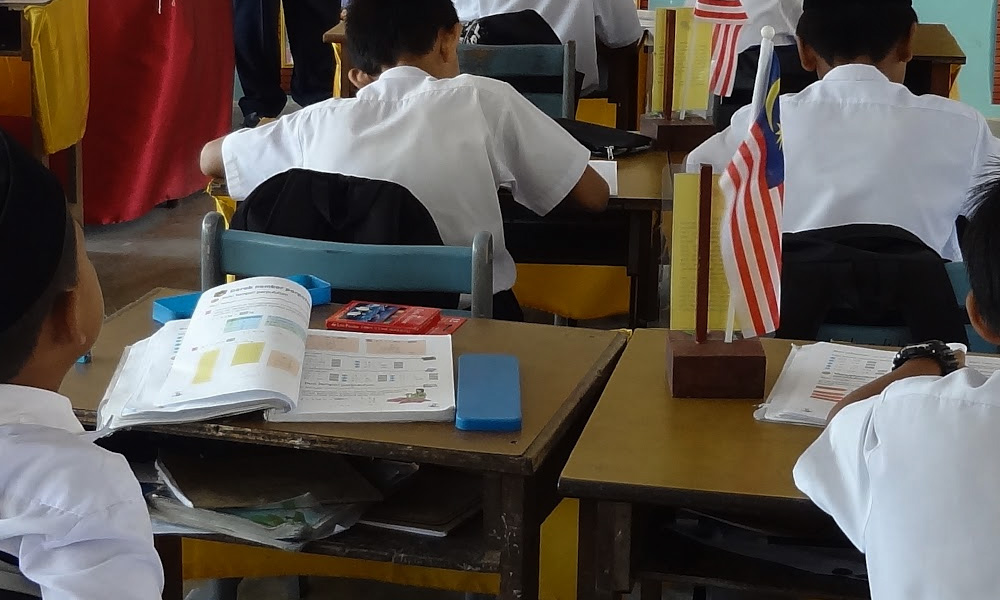

The assumption behind such a perspective is that our education system has encouraged ethnic segregation and as a consequence, the majority of the students are only exposed to their own ethnic members and most of them don’t have close friends from other ethnic groups. Official figures confirm that the majority of our primary school students study in a more or less ethnically homogenous environment.

Nonetheless, we often forget that this is not so in secondary schools. Government statistics report that in 2011 around 88 percent of secondary students study in national secondary schools, whereas Chinese independent schools enrol about 3 percent of the students, and government-aided religious schools, 4 percent of all the students.

In other words, the great majority of our secondary students has studied in the national schools. Many would have had the opportunity to study with classmates from other ethnic groups.

Is it not more sensible then to ask why five years of schooling in a single-stream secondary education does not foster national unity, rather than always focusing on the primary education?

In fact, single-stream education does not render all secondary schools ethnically heterogenous, as there are other factors affecting student composition such as the demographic distribution and geographical location of the schools. The same situation would apply even if we have a single-stream primary schooling system.

On the other hand, is there empirical evidence which confirms that inter-ethnic interaction would improve inter-ethnic relations? The commonly cited social psychological theory in support of this hypothesis is the contact theory propounded by Gordon Allport in mid-1950s, who proposed that contact could reduce intergroup prejudice if specific conditions of interaction are fulfilled.

More than 50 years after, numerous survey findings worldwide could only confirm that a positive attitude toward an outgroup is frequently found to be associated with the extent of interaction or friendship link with members of the outgroup.

Nonetheless, the findings are inconclusive as to whether it is the positive attitude which has led to greater intergroup interaction, or the interaction which has led to a reduction of prejudice.

In addition, though the statistical relationship between contact and prejudice is indisputable, it is not a very strong one. This means that other social factors may explain better inter-ethnic prejudice or antipathy than the extent of inter-ethnic interaction.

In public discourse, people often point to the ethnicised pattern of interaction in university campuses as indicating ‘ethnic polarisation’. This is a rather superficial and speculative way of interpreting the pattern of interaction as necessarily indicating a hostile or negative inter-ethnic perception.

Some commentators blame it on the lack of experience in inter-ethnic interaction of these youth, but a couple of surveys found that youth respondents did not indicate any great unease in relating to someone outside their ethnic groups.

A review of past studies on the extent of inter-ethnic interaction in Malaysia, especially on university campus, reveals that inter-ethnic interaction has always been limited as far back as the 1960s. This includes those youths who were mainly educated in English medium schools, as indicated by a survey conducted in the University of Malaya in 1966/7.

Another survey, involving more than 7,000 secondary students between 1968 and 1969, found that inter-ethnic mistrust was the highest among secondary students in ethnically heterogeneous, prestigious English-medium schools, and not in ethnically homogeneous Chinese-conforming schools (which evidently had a lower level of inter-ethnic interaction).

The scholar found that this was due to a heightened awareness and sense of competition generated by the racial preferential policy implemented by the government, and magnified by the frequent inter-ethnic exposure in the former case.

In other words, even if these students from English medium schools might feel much at ease with inter-ethnic interaction due to frequent contact, their anxiety for their future social mobility prospects appear to have overshadowed any possible reduction of prejudices against their ethnic outgroup.

In Singapore, even though the government has enforced ethnic integration in public housing allocation and school enrolment, a survey conducted among 4,400 primary school pupils in 2003 found ‘minimal inter-ethnic mixing’ during school recess. Preference for friends of the same ethnic origins became more pronounced among primary six pupil, when compared with primary three pupils.

This pattern of ethnic re-segregation in integrated schools is also observed in several other studies conducted elsewhere in the world.

In short, it is too simplistic to think that a single-stream education would be able to resolve ethnic division and conflicts in Malaysia. This position is not grounded on empirical evidence.

The phenomenon of ethnic relations is multi-dimensional and inter-ethnic interaction is only one aspect of a larger, complex societal dynamic.

This is not to deny the benefits of a greater extent of inter-ethnic interaction, which may inculcate a greater understanding of other ethnic groups and intercultural competency.

But politicians, who are rabble-rousers, are so, not because they have insufficient experience of inter-ethnic interaction. By limiting our analysis of ethnic division to an interpersonal level, we miss other crucial social dimensions which shape inter-ethnic relations in equally powerful ways.

HELEN TING is Associate Professor at the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.