FEATURE | As early as the 15th century, the Bajau Laut moved around freely in the Sulu Zone – the area around the Sulu Sea and Celebes Sea – until the concept of national borders came into being.

Many chose to stay on land in the emerging nation-states, while others chose to roam free at sea.

But the descendants of the latter – often referred to as ‘sea nomads’ or Sama Dilaut, a sub-group of the Sama-Bajau – are finding their movement and access to livelihood becoming increasingly restricted. Many eventually end up stateless, just like Unggun.

Unggun has been living in a traditional Bajau Laut houseboat on the waters off Semporna for most of his life, after fleeing from Tawi-Tawi at a young age.

Still living without electricity, he and his family seem to be excluded from many aspects of modern life – they do not, for instance, know about the regime change on May 9, and not even the time, nor their ages.

Nonetheless, Unggun doesn't see education as a way to improve his community’s livelihood.

"I don't think so," he says, almost defiantly, when asked whether schools on houseboats would be of any help. "Other Bajau Laut people may go to school, but we don't."

Despite access to education being essential for the next generation of Bajau Laut to adapt to modern life, Unggun believes the only skill worth learning is fishing, knowledge of which he has passed down to his four sons.

Schooling at sea

Iskul Sama Dilaut Omadal, a community-based school on Omadal Island, has been providing basic education for stateless Bajau Laut children since 2015.

Its principal, Roziah, estimates that there are about 500 people on the Island, including those living in stilt houses and on houseboats.

Of the 35 students, aged seven to 12, only one is from a houseboat family – indicating that parents in the five or six nearby houseboats are reluctant to give their children a more formal education.

"We Bajau Laut people are used to this (marine) life," Unggun says. "Sometimes, they may not adapt to regular school life."

As Roziah says, "The houseboat Bajau Laut families may take their children to other places for fishing. If their parents are looking to make a living, I can’t stop them."

She points out that even the solitary student from a houseboat family only attends school once or twice a month, despite her multiple attempts at advising his parents.

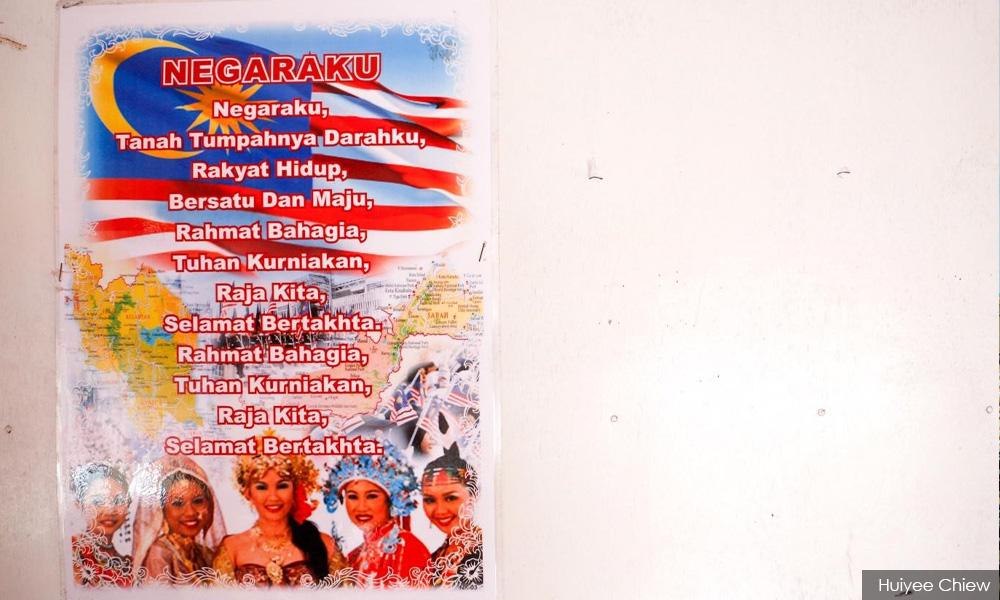

Facing a seemingly lost cause, Roziah's job is made more difficult by the fact that the students learn about Malaysia, but are not even Malaysians.

"We teach them Bahasa Malaysia, about the national flag, the states and every festival as if they are citizens, but they are not. But we must at least let them know ‘This is what Malaysians are like.'"

Iskul still considers them Malaysians, even if they are not recognised by the state.

Roziah believes this is a preparatory – and necessary – process for them to become Malaysian citizens one day. Or at least, to enable them to communicate with other Malaysians, and no longer remain invisible and voiceless.

"We want them to know they are valued by the government and the local community. If the government knows who they are, then maybe they won't look down on themselves," she says.

Of course, the ideal situation is for these children to obtain citizenship, or at least, proper documentation. As Roziah recalled one parent asking her, "If my child can read and write, but he still gets caught when he works on land, why should he be educated?"

The complexity of citizenship

Sanen Marshall, who teaches politics at Universiti Malaysia Sabah, describes the complexity of the houseboat Bajau Laut obtaining citizenship.

"One reason for this is that those living on the houseboats have been inadvertently left out of earlier political and bureaucratic initiatives to process identification," he says.

"Secondly, there were Bajau Laut families that began to move back and forth between Sabah and the Philippines since, or even before the Second World War.

"For example, there is one family with 12 children. The first six were born in the Philippines, the seventh and eighth in Sabah, and the rest in either one of the two countries. So, is the family Malaysian or Filipino?”

Malaysia has strict prerequisites for citizenship, such as a marriage certificate and the child's birth certificate.

But those in the houseboat Bajau Laut community do not normally possess marriage certificates, and even if they do, it may not be formally recognised. In order to register a birth, certification from hospitals must be obtained, or at least from midwives or doctors.

Aside from the cost of travel, some Bajau Laut are not willing to risk deportation and make their way to the only hospital in Semporna.

Some cannot afford the delivery costs, even if they are aware of the importance of a birth certificate. To others like Unggun, the concept itself is alien.

As a result, many Bajau Laut are trapped in a vicious cycle of statelessness, passing it from generation to generation.

"If the Philippine government declares that certain Bajau Laut found within Malaysia’s borders are their own people, I don’t think Malaysia will issue citizenship, since they are recognised by another country," Marshall points out.

"Otherwise, the obligation will fall on Malaysia to recognise all Bajau Laut, a number of whom share a closer cultural affinity with island communities that are located far afield near Mindanao, rather than communities in Sabah or even Tawi-Tawi.”

The inherited statelessness of the Bajau Laut seems arduous to resolve. It requires collaboration between Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia to study the community's cultural diversity, complexity and mobility. But it is nevertheless vital, as being stateless leaves them excluded from basic protections and rights.

The language barrier, remote locations and nomadic lifestyles have caused them to be out of sync and largely invisible to the rest of the world. So where will they end up?

'I am Sama-Asli'

Sitting on the deck of his houseboat as rays of sunlight bounced off the green waves, Unggun says he will stay exactly where he is.

"I will stay here, it is peaceful here," he says when asked what he would do if given identity documents by the Philippines.

In the eyes of the Bajau Laut fleeing from the south of the Philippines, Semporna – as its name would suggest – is peaceful, a place without war.

"The government here does not harass us. They only arrest us if we create problems," Unggun says. This is why he feels safe here, and why statelessness is a distant concern.

Despite knowing that having identity documents would remove the risk of being arrested on land, he says, with a note of helplessness, that he still wouldn't know how to read even if he did have an IC.

The things most take for granted – belonging to a state, having documents – seem dispensable to Unggun, perhaps as a result of it being out of reach.

When asked whether he considers himself Filipino, Indonesian or Malaysian, he exclaims, proudly, "Sama, Sama-Asli" – with 'sama' meaning 'together' and 'Asli' meaning 'indigenous'.

Unggun doesn't consider himself stateless; rather, he believes that no country is his. Except the one not recognised by any state, the boundless and borderless ocean.

The Mandarin version of this article first appeared in The Initium Media.

PREVIOUS

Bajau Laut: Once sea nomads, now stateless

RELATED REPORTS

'An invisible jail' - stateless children in Malaysia

Aina’s story: Why M'sia needs to rethink how it treats institutionalised children