Malaysiakini's coverage to mark the 50th anniversary of the May 13 riots has received both praise and criticism.

Those who appreciated the work commended the portal for its courage and the use of technological tools to tackle an issue long deemed taboo.

Others - including those circulating photographs and details of social media accounts belonging to the journalists who worked on the project - believe the coverage is lopsided and misleading.

This article will address the criticism because, as a news organisation, Malaysiakini believes in transparency, and values the views of its audience, be it bouquets or brickbats.

Motivation

The first is obvious - because it is the 50th anniversary of the May 13 incident and a retrospective piece was warranted.

We sought to fill the vacuum due to the general silence imposed on the topic, so that it would not be exploited with disinformation for malicious purposes.

We were also anchored by the intention to revisit this incident for those born after the riots so that they could learn from this tragic episode and not repeat past mistakes.

Balance

To mitigate against ethnic bias, we ensured the team was multi-ethnic.

However, because the project was aimed at young Malaysians - a group whose knowledge of the incident is scarce but who has to bear its stigma all the same - the bulk of the team was aged 35 and below.

We also sought to balance the divergent narratives surrounding May 13.

On one end of the spectrum is the view that the riot was a spontaneous act of communal violence, sparked off by the behaviour of opposition supporters celebrating the results of the 1969 general election.

On the other end is the view that it was politically orchestrated as part of a coup d’etat to oust the then prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman.

The team tried to balance the articles by referring to the official account of the events by the National Operations Council (Mageran), newspaper articles published at the time and key academic publications and books about the incident. A full list of our references can be found on our special page and at the end of this article.

The team also conducted interviews with eyewitnesses and their accounts were compared to the documents above to ensure that the timelines and locations were plausible. If they contradicted other accounts, the portion of the testimony was removed.

Portions which could not be corroborated were only published if they did not diverge from the Mageran timeline, make grave and unsubstantiated accusations or have severe connotations.

The same was applied for incidents which witnesses said they heard had happened, but did not see for themselves.

The team also held lengthy discussions over the use of certain terms. For example, we opted for 'May 13 riots' and not 'May 13 racial riots' so as to not take sides in the competing narratives on whether it was spontaneous communal violence or a politically-orchestrated incident.

Why were some events not included?

Among the most frequently asked questions following the publication was - why was the violence or provocation against one ethnic group not reported? The short answer is, it was. Another question is - why was only one ethnic group depicted as violent? The short answer for that is, it was not so.

The impression is due to certain quarters peddling this claim, choosing to only post screenshots of incidents of Malay violence published by Malaysiakini on social media. But this is not an accurate representation of the coverage.

For example, the killing of Malays in cinemas was included in the special page, as were the jeers by Chinese bystanders against a passing Malay crowd, which led to the first clash on May 13.

One eyewitness talked about fishing out bodies of Malay victims from the river and a dumpster, while another spoke about seeing one opposition supporter flashing Malay bystanders. Another talked about Chinese gangsters plotting to kill his Malay neighbours.

Similarly, we published witnesses' accounts of Chinese homes being razed and how two Chinese men passing by in a van were killed. The latter was a testimony cited from the Mageran report.

These are graphic and disturbing details, but we included them in the interest of completeness. They were also the first-hand experiences of the witnesses or cited in the key references.

There is, however, an oft-spoken incident said to have taken place in an open air cinema in Pudu involving Chinese victims. We could not publish this because we found no eyewitnesses who could attest to being there when it happened, only that they heard about it. The documents referred to did not mention this incident either.

The fact is, the victims were both Chinese and Malays and so the violence was perpetrated by both sides. Malaysians of other races were also among those on the casualty list.

At the same time, there were good Samaritans on both sides of the conflict, who helped each other despite their differences. In the final analysis, we all lost.

To note, working on this project, the team compiled a blow-by-blow chronology which had 109 events. In the interest of the reader's experience, we only published the gist of that list - 18 events - which we believed were crucial to the timeline.

Why did Malaysiakini show that more Chinese than Malays were injured or killed?

Because that is the fact.

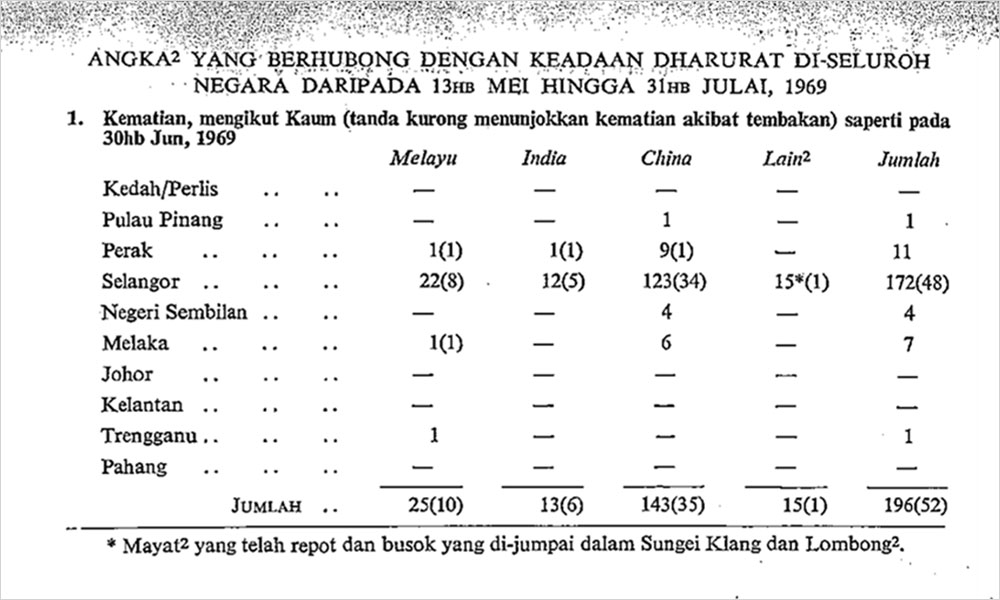

Many of our critics baulked at the infographic showing this. They insisted that we should have referred to the Mageran report to publish only the established facts. Here is a fact: The statistics came from the Mageran report.

The report sold to the public in October 1969 did not mask that truth, and neither should we, 50 years later.

Is Malaysiakini trying to say the Malays or the Chinese were at fault?

At this juncture, it is important to note that the project's objective was not to assign blame or to find out why the riots occurred. The special page, in particular, was focused on establishing only what had happened on the first day of the riot - May 13, 1969. (The riot went on for many days after.)

However, journalism is about putting things in context.

This is why the events of May 11 and 12 were dealt with in the introductory paragraphs and images of the victory parades by opposition supporters were included to depict the tension in the city. (The same treatment was given to the aftermath and impact on public policy.)

We did not include a picture of the body of Encik Nasir, an Umno worker who was killed in Penang, because our editorial policy is not to publish photographs of dead bodies. Similarly, we did not publish photographs of the Labour Party worker killed in Kuala Lumpur around the same time.

However, both incidents were mentioned at the beginning of our special page.

Is Malaysiakini trying to spark another riot?

Actually, quite the contrary.

These articles sought to uncover the facts surrounding an incident, which five decades later, is still exploited by politicians to stoke fear and further their respective political agendas.

As a nation, we cannot pretend this incident did not happen. For it is from such mistakes that we learn to appreciate the importance of racial harmony and recognise the dangers of divisive politics.

Are we done?

Not yet. The May 13 riots are part of our collective personal histories. The stories have been passed down for generations, but never truly recorded.

Many of the eyewitnesses we spoke to are in their 70s. Malaysia's average life expectancy rate is 75. This might be our last window of opportunity to record these oral accounts. We hope you share your story with us, too.

There are also classified documents which have not been released to this day - 50 years after the event. So there is still a long way to go before we can get an accurate account of what transpired.

But this is Malaysiakini's attempt to make use of all the available information to shed some light on an incident that continues to haunt Malaysians. Never forget, never repeat.

Below is a list of our references:

The May 13 Tragedy: A report by the National Operations Council (1969)

May 13: Declassified Documents on the Malaysian Riots of 1969 by Kua Kia Soong (2007)

13 May 1969: A Historical Survey of Sino-Malay Relations by Leon Comber (1983)

May 13, Before and After by Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj (1969)

The Kuala Lumpur riot and the Malaysian political system by Anthony Reid (1969)

Malaysia: Death of democracy by John Slimming (1969)

The May Thirteenth Incident and Democracy in Malaysia by Goh Cheng Teik (1971)

The Deadly Ethnic Riot by Donald L Horowitz (2001)

May 13, 1969: Truth and reconciliation by Martin Vengadesan, The Star (2018)

Various articles published by the Straits Times in May 1969