COMMENT | Introducing some form of revenue collection from the rakyat to help defray healthcare costs has been on the government’s agenda since the 1980s.

They have toyed with the idea of a special health tax, a separate health financing authority, a payment system that covers both the public and private sector and others, but so far, despite many studies, no definite plans have been finalised.

This present episode of sponsoring health insurance for the B40 appears to have started from the Skim Peduli Sihat implemented by Selangor in 2017.

Under the scheme, families with a household income of RM3,000 and below receive a debit card which will pay for treatment at any private healthcare facility in the state up to a maximum of RM500 per year per family, limited to RM 50 per treatment episode.

This idea was incorporated in the Pakatan Harapan manifesto, which lists the scheme as one of the 10 targets for the first 100 days. However, the idea seems to have morphed into something bigger and more harmful.

In August this year, Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad announced that the government would introduce social health insurance for B40 families, and that these families would not be asked to pay towards the scheme.

This insurance will pay for a total of RM10,000 worth of treatment in private hospitals for that family for one year. According to Dzulkefly, this new plan will be rolled out in January 2019.

Impact on federal health budget

We now have about 7.5 million households in Malaysia. Forty percent of that would be three million families. If all of them were to utilise their entitlement to insurance cover, that would come to whopping RM30 billion a year. This is bigger than the federal health budget for 2018 – RM27 billion.

Of course, not every family will use their entitlement in a year, but we should not underestimate the innovative approaches that private hospitals might take to milk this cash cow.

Patients can be easily persuaded or frightened into getting themselves admitted for scopes, MRIs and angiographies, as there is a huge asymmetry in knowledge between patients and their doctors. Health expenditure will go up, but it may not really add appreciably to better health for the population.

Dr Lee Boon Chye, the deputy minister of health, commented a few days later that families that wished to do so could purchase additional coverage if they wished.

But things are not all that simple.

How are insurance payments to be determined? Will insurance premiums be community rated? This means that every family pays an amount irrespective of the medical history of the family members. This is the system adopted in South Korea, where people have to pay five percent of their income to the insurance fund.

Will there be a single not-for-profit insurer as there is in South Korea, or a number of private companies competing with each other for the market as is the case in Malaysia now? And in Malaysia the premiums are risk-rated. In other words, if you have diabetes, or if you have a history of certain illnesses, then your premiums will be higher.

The second issue that we have to consider is how this insurance scheme will compensate the healthcare provider. There are two ways this is done – by a fee for each service provided, or by a capitation scheme.

The GP system in the United Kingdom is done by capitation – each GP is allocated a number of patients to look after, and the GP is paid monthly by the number of patients he is looking after whether or not they come to see the doctor that month.

One benefit of the capitation system is that it makes sense for the GP to do health education, so his patients’ chronic conditions are well under control and they do not develop complications that require further hospital visits.

The fee-for-service system pays the health care provider based on the number of visits, procedures, and types of intervention that he provides. If not properly audited patients may end up being over-investigated, and subjected to procedures and operations that they might not really need.

For example, a child presenting with pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, mesenteric lymph node inflammation has to be considered as the differential diagnosis to appendicitis. But as charges for managing the former conservatively are much less than operating as the latter, a fee-for-service will influence doctors to go for the latter diagnosis.

Or say a patient with chest pain seems like he needs an angiogram, especially if the pain is not related to exertion and there are no other risk factors. But reassuring a patient is not as lucrative as performing an angiogram – and quite a few doctors will succumb to that temptation.

Some of this is already occurring in the private sector in Malaysia. And there are many other examples.

Two-tiered healthcare system

The development of private hospitals has undermined the public healthcare system. We already have a two-tiered healthcare system in Malaysia where those who can pay for treatment in private hospitals get to meet specialists promptly and get treatment much faster than those relying on government hospitals.

This is one of the reasons why several health activists are alarmed by the health minister’s enthusiasm in pushing for this new insurance scheme without taking more time to evaluate all its potential ramifications.

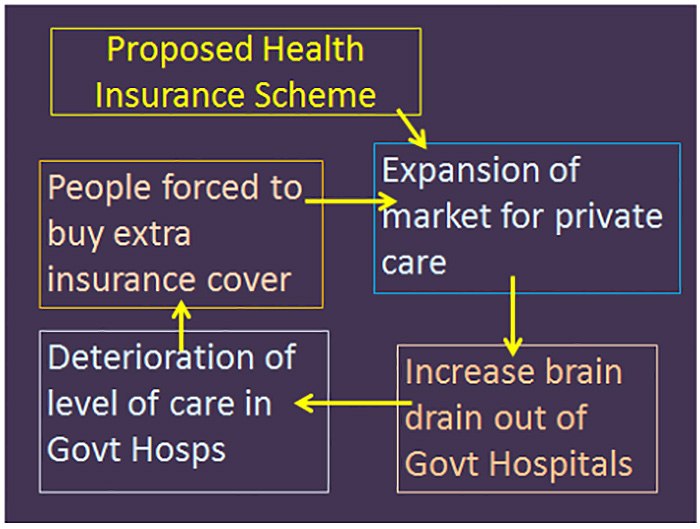

We are anxious that the following set of events will be set into motion:

PSM believes that at this point in time we need to take every step to preserve and strengthen the public healthcare system in our country.

We feel that, in addition to playing an important role in treating the sick, it also builds a sense of social solidarity among the different classes of people in this country, reduces anxieties regarding catastrophic illnesses and old age, and creates the conditions for people to be more generous to each other.

In short, it makes Malaysia a more happy and harmonious society.

PSM calls on Putrajaya to submit the social health insurance scheme to greater scrutiny and discussion before taking any definite decision. We would be doing a disservice to the poorer half of the population if we were to rush to implement this new insurance.

The federal health budget should also be increased in stages over the next five years to four percent of GDP from its current 2.2 percent.

The extra funds can be used to build a second general hospital in all state capitals that have overcrowded wards, and to provide plates, screws, operating staplers, cataract lenses, drug-eluting stents with minimum co-payments.

We claim to be aspiring to be a high-income country. The UK, with its per capita GDP of US$44,100 (PPP), spends 9.9 percent of GDP on healthcare, while we on US$29,000 per capita spend only four percent of GDP overall.

There must also be a moratorium on the building of new private hospitals, as these will continue to suck away specialists from the government sector. This moratorium could be lifted once a better balance in the deployment of our specialist doctors is achieved.

PSM also calls for the introduction of a service commission for healthcare personnel in government service with features that will help retain senior and experienced people.

This commission could perhaps adopt the pay scheme in the National Heart Institute, institute three-month sabbaticals to specialists for every five years of service so that they can go overseas and pick up new skills and procedures, as well as provide enhanced pension for those specialists who put in 20 years or more of service in the government sector.

Some Malaysians might think that this would make the B40 'lazy.' But apart from the 'externalities' mentioned above, one other reason is that Malaysia is trapped in a low wage economy where ordinary workers are paid much less than their compatriots in advanced countries, despite having similar productivity.

Workers in the electronic factories in Bayan Lepas receive about an eight of the pay of a worker in a US factory in California, even if they are producing the same component product.

This differential has little to do with "productivity", as the World Bank and IMF would like us to believe, but is due largely to the market power of the large firms outsourcing production of components to developing countries. But this is not the place to go into a detailed discussion of that.

Since we are unable to pay fair monetary wages to our workers given our subservient position in the international economic system, the least we can do is to provide them essential services – health, education, public transport – at subsidised rates.

A sort of "social wage", if you will.

DR D MICHAEL JEYAKUMAR is the former MP for Sungai Siput.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.