COMMENT | When the first redelineation recommendation was issued for public review in September 2016, there was immediate uproar from both sides of the political divide. The public was reminded of terms such as gerrymandering and malapportionment that, already rife, were made even worse by the Election Commission’s proposals.

The public was faced with the reality that any attempt to change the federal government in Putrajaya would be a herculean task. The redelineation of 2016-18 was marked by increased racialisation, unequal constituency sizes and seats favouring BN. It was an adamant survival ploy by the then-longest ruling party in the democratic world.

The redelineation exercise of 2016-2018 continued the non-compliance or aggravation of non-compliances with the 13th schedule of the constitution.

Though flawed, the 13th schedule has laid the framework for when the EC ought to conduct redelineation exercises and how they should be done. The two key fundamentals in the 13th schedule are respecting the local ties and ensuring constituency populations are nearly equal.

By rule, the EC ought to rebalance all constituencies and rectify any violation of local ties, or changes in administrative boundaries in any redelineation exercise. However, the EC failed to do so, and refused to comply despite all the court cases thrown at it.

How is it that the latest redelineation exercise did not prevent BN from losing Putrajaya?

Tindak Malaysia’s 2013 studies had previously concluded that every redelineation exercise resulted in a temporary booster for BN’s hold on Parliament.

However, our calculations this year prior to May 9 came to the immediate conclusion that the redelineation of 2016 would not have much impact on the results of the 14th general election. This article will identify some key factors that explain how the rigging of electoral boundaries was defeated.

Dramatic changes of political preferences

The 2016 redelineation exercise, like its predecessors, was built on faulty premises based on historical voting trends.

Since Malaysian voters tend to vote across ethnic lines, racial gerrymandering has become pronounced since 1984 (as allegedly acknowledged by ex-EC chief Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman).

The 1984 redelineation exercise (including the creation of new seats) resulted in more Malay-majority seats being created. Previously, Malay voters solidly backed BN. The 1994 redelineation strengthened the presence of Muslim bumiputera voters in Sabah to disadvantage the then-powerful opposition party in the state, Parti Bersatu Sabah.

The sacking of then-deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim in 1998 and resurgence of PAS in 1999 may have sent a signal to EC that Malay votes were shifting in favour to PAS. The 2003 redelineation exercise resulted in more mixed seats to dilute the opposition Malay vote bank.

Changes to seat count and boundaries were one of the reasons why BN scored the biggest victory in 2004.

The only problem with racial redelineation is it increases the gamble for potential victors and losers (as political analyst Wong Chin Huat mentioned in December 2017).

The 2016 redelineation exercise was done when multi-cornered fights still favoured BN and there was continued strong support for BN in Sabah and Sarawak. However, many court cases delayed the implementation of redelineation recommendations for nearly two years. This may have given much breathing space for Pakatan Harapan and newly formed Parti Warisan Sabah to gain traction.

Historic dominance over media and religious institutions allowed Umno to control the mindset of rural sectors for decades. By carving out undersized seats (as preserved in the 2016 redelineation exercise), it created a bank of dependable seats for BN over the decades, including in the 13th general election.

In the run-up to GE14, Harapan and Warisan made breakthroughs in the BN heartlands through social media and the presence of outstation voters. Combined with crippling living costs and anger with extravagant spending by then-prime minister Najib Abdul Razak, the rural sector began to explore other political alternatives to Umno.

The mathematics to ensure a secure BN victory with the aid of redelineation began to backfire.

The parliamentary seats untouched by redelineation such as those in Sabah, Kedah, Perak and Pahang were becoming more vulnerable to political shifts in a multi-cornered fight environment.

Let’s look at two examples – Selangor and Lembah Pantai.

Selangor

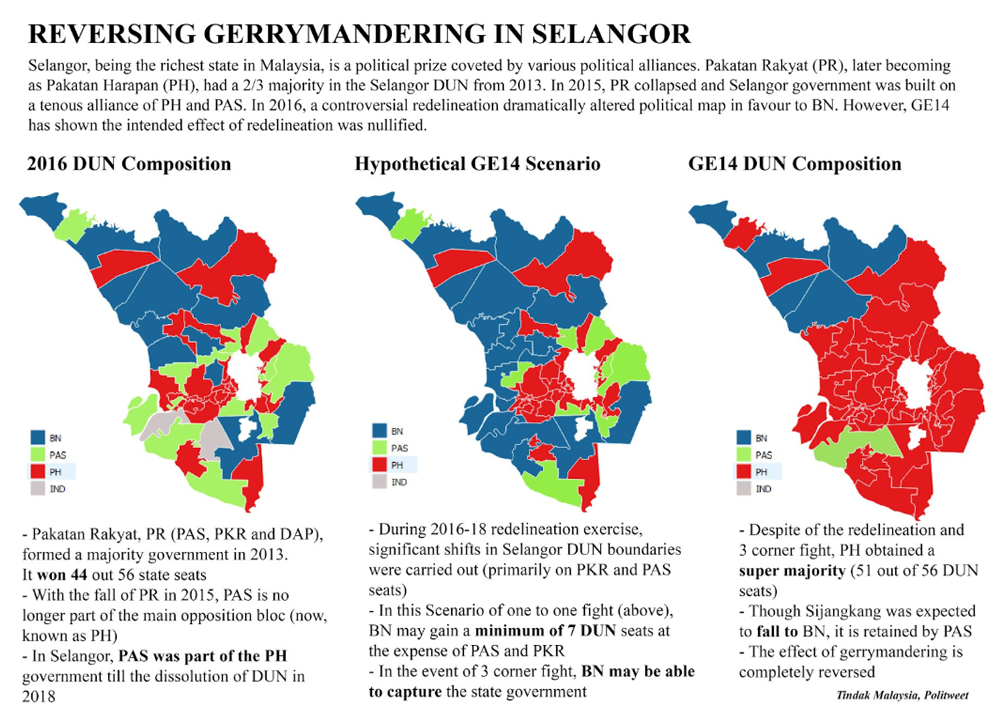

Of all the states, Selangor experienced the biggest shifts in electoral boundaries both at the parliamentary and state assembly level.

The approved proposals (despite multiple court cases and objections) resulted in much of the Harapan votes being packed into safe DAP seats (and PKR’s Subang) while softening PAS, PKR and Amanah seats for potential BN takeovers.

Due to the rigged redelineation, Politweet computed that BN would capture Selangor with a thin majority in the event of a three-cornered fight.

What many commentators may not have highlighted were the seats that were not touched by redelineation, and some which were undersized, in Selangor. State seats such as Hulu Bernam (undersized), Batang Kali, Sungai Burong (undersized) and Dengkil (undersized) either witnessed a drop in BN majorities or were taken over by Pakatan Harapan in GE14.

Undersized seats refers to seats with small populations, which tend to be in areas that are rural or which were previously BN strongholds.

Similarly, the untouched BN parliamentary seats such as undersized Sabak Bernam and Hulu Selangor were up for grabs by Harapan.

In short, the redelineation could not stop the swing towards Harapan that nearly obliterated BN both at the parliamentary and state level.

Interestingly, the gerrymandering of Sijangkang, which could have resulted in BN seizing the seat, failed miserably as PAS retained the seat in GE14.

The Institut Darul Ehsan (IDE) surveys of January 2018 and Invoke surveys of Selangor from March 2018 indicated a dramatic shift of political preferences among Malay and Indian voters. 10 years of Harapan rule and the urbanised nature of Selangor may have contributed to the higher confidence in voting for Harapan.

The stalled redelineation report, despite finally being pushed through by ignoring the objections raised, may just have raised voter awareness and determination to the point of creating a Harapan supermajority for Selangor.

Lembah Pantai

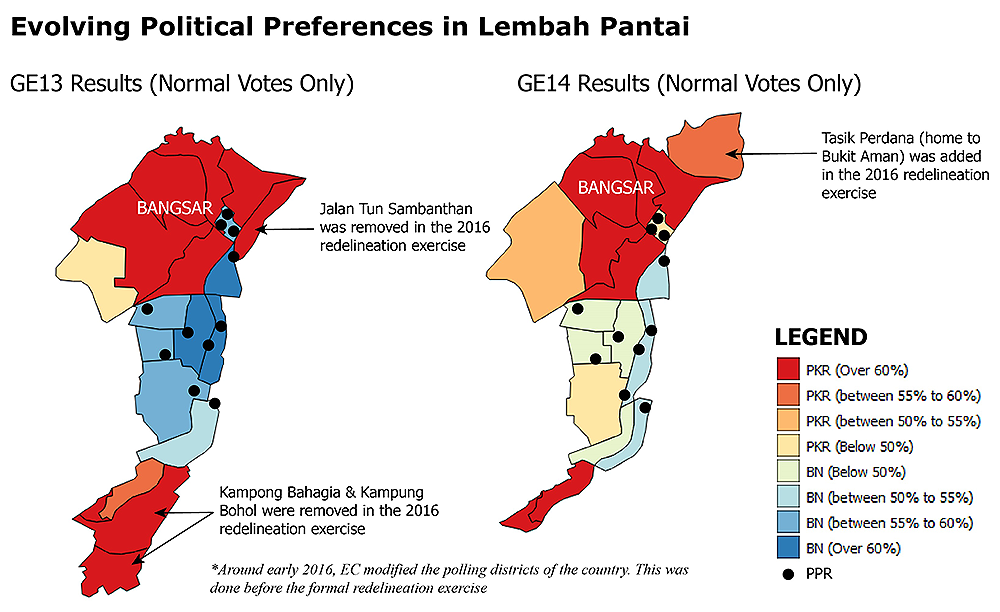

Lembah Pantai witnessed PKR’s Nurul Izzah Anwar slaying BN giant Shahrizat Abdul Jalil in the 2008 general election. This seat is a gerrymandered seat that is home to upper-class Bangsar, low-income People’s Housing Programme (PPR) areas and housing estates down south.

The 2016 redelineation exercise resulted in Bukit Aman, located within the Tasik Perdana voting district, with its bulk of BN votes being added into Lembah Pantai while two to three Harapan districts were excised from the seat. The addition of nearly 7,000 police voters could shift the electoral outcome of GE14 for this marginal seat.

In this case, how did PKR’s Fahmi Fadzil, a fresh new candidate, win a bigger majority despite the gerrymandering? The intended effect was defeated on two counts – varied turnout in the seat, and changes in political preferences even among the uniformed servicepeople.

Despite the addition of Bukit Aman, police voter turnout for GE14 was five percent below constituency average and BN lost 13 percent of votes due to shifts in political preferences.

Normal votes refers to the voting process on the final election day. Voters are allocated to the polling district and must vote in that particular area.

In Bangsar, while the turnout was below average, Harapan support grew by 10 percent. However, it was in the PPR area where the shift in political preferences was very apparent. BN lost around 10 to 15 percent of their votes in the PPR areas, mostly to PAS. Turnout in PPR areas was close to or above average.

Varying turnouts in the constituency and political shifts defeated the intended effect of redelineation and the presence of suspicious voters in Lembah Pantai.

Next, we shall look at the impact of the absence of new seats in the current redelineation exercise.

TOMORROW

Part II - The impact of the absence of new seats

TINDAK MALAYSIA is a pro-electoral reform NGO committed to uniting Malaysians through socio-economic empowerment programs. Tindak Malaysia has led a nationwide training programme for polling and counting agents since 2008, pioneered Malaysia's first civil society initiative to draw fair electoral boundaries, and is now committed to an open data program.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.