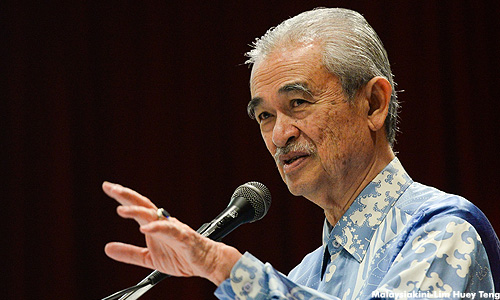

This interview with economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram, former assistant secretary-general for economic development at the United Nations, was conducted in August for publication in the run-up to the country’s next Budget for 2018 due to be announced next Friday.

Developed country status

Question: Malaysia is close to achieving developed country status and is growing at a reasonable pace. Why are you concerned then?

Jomo: Becoming a developed country involves much more than achieving high-income status. But even by reducing ‘developed country’ status to becoming a ‘high-income’ country, we are not quite there unless we resort to statistical manipulation, for an example: by using 2013 exchange rates, or by ignoring about a third of the labour force who are ‘undocumented’ foreign workers.

For example, the ringgit declined from RM3.2 against the US dollar in 2014 to almost RM4.5 before recovering to the current RM4.2! But then we continue to use the old exchange rate or purchasing power parity (PPP) to pretend that we are almost there. The only people we are cheating is ourselves.

Also, if we continue to grossly underestimate the number of foreign workers in the country, then the denominator for calculating per capita income goes down. Similarly, by excluding the lowest paid foreign workers, income inequality has been declining when their inclusion may give a different picture. Thus, we can reach supposed high-income status more quickly if we pretend there are only one or two million foreign workers, when even the minister admitted last year to about 6.7 million!

Seven million, mainly undocumented foreign workers in Malaysia comes to over a third of the country’s total labour force. Many of them work and live in far worse conditions than the worst-off Malaysian workers. We are thus dependent on a huge underclass, largely foreign, whom we are in denial about.

New Economic Model

What do you think of Prime Minister Najib Razak’s New Economic Model?

Jomo: Let us be clear about this. The New Economic Model, or NEM, is really a wish-list of economic reforms desired from an essentially neo-liberal perspective. That does not mean it is all good or all bad. It contains some desirable reforms, long overdue due to the accumulation of excessive, sometimes contradictory regulations and policies.

Although the NEM made many promises and raised expectations, most observers would now agree that it has rung quite hollow in terms of implementation despite its promising rhetoric. As we all know, the NEM was dropped soon after it was announced for political reasons, and has never been the new policy framework it was expected to be.

Turning to actual policy initiatives, to the current administration’s credit, it accepted the minimum wage policy and BR1M (Bantuan Malaysia 1Malaysia) idea, both long demanded by civil society organisations, and supported by many, mainly opposition parties. The minimum wage policy has probably been far more important than BR1M in improving conditions for low-income earners.

Premature deindustrialisation

The contribution of manufacturing to growth and employment has been declining in this century. Yet, you seem to be nostalgic for industrialisation when the leadership wants to move to tertiary activities.

Jomo: Sadly, instead of acknowledging the problem, ‘premature deindustrialisation’ is being cited as proof of Malaysia being developed although services currently account for most job retrenchments.

Indeed, Malaysia has been deindustrialising far too early, even before developing diverse serious industrial capacities and capabilities beyond refining palm oil and so on. We have abandoned the past emphasis on industrialisation, but have not progressed sufficiently to more sophisticated, higher value-added industries.

In Japan, South Korea and China, policies to nurture industrialists and other entrepreneurs to become internationally competitive, enabled these countries to grow, industrialise and transform themselves very rapidly.

We are suffering great illusions if we think we can leapfrog the industrial stage and go straight to services. We should not try to emulate Hong Kong because we are a different type of economy. Even Singapore has not gone the Hong Kong way and continues to try to progress up the value chain in terms of industrial technology.

We need to stop blindly following policies espoused by international institutions. GST (Goods and Services Tax) is a variant of value-added taxation, long promoted by the IMF (International Monetary Fund). To accelerate progress, we need to develop better understanding of the Malaysian economy – of its real strengths and potential, rather than assuming that the current mantra in Washington is correct, let alone relevant.

Middle-income trap

According to the World Bank and others, Malaysia is stuck in a middle-income trap. The argument is that the NEM as well as financial services development are needed to get out of it.

Jomo: The idea of a ‘middle-income trap’ is due to Latin American and other countries uncritically following Washington Consensus prescriptions promoted by the Bank and the IMF. The promise is that following their prescriptions would lead to development.

Key elements of our own ‘middle-income trap’ are actually of our own making, e.g., by giving up so quickly on industrialisation. The prescriptions imagine we can somehow leap-frog to accelerate development without making needed reforms.

The NEM and current official development discourse emphasise modern services, especially financial services, for future growth. But why would investors want to come here rather than, say, Singapore? If they want lower costs, there are other locations.

To offer tax breaks or loopholes, or to make Malaysia a tax haven, the question again is why come here rather than Singapore.

And how much has the national economy really benefited from the Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre? Do we need to keep making the same errors?

Looking at other international financial centres, it is not clear that it will be a net plus for the country, and provide the basis for sustainable development suitable for an economy like ours. Remember, we are no Hong Kong.

Historically, we have been heavily dependent on foreign direct investment, not for want of capital, but for access to markets, technology and expertise. To make matters worse, over the last decade, foreign investors have taken a growing share in publicly listed companies, helped by the falling ringgit in recent years.

Arguably, foreign ownership of the Malaysian economy has never been as high since the 1970s. As large corporations are increasingly dominant, they have often crowded out small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and other Malaysian firms.

Macroeconomic management

In his recent book, Dr Bruce Gale (author of ‘Economic Reform In Malaysia: The Contribution Of Najibnomics’) has praised current macroeconomic management.

Jomo: Well, Gale is a political consultant and needs to ‘cari makan’. He is not a serious macroeconomist the last time I checked, but should nonetheless be taken seriously because he reminds us that well-managed ‘public relations’ influence market and public sentiment, including credit and other ratings. He heaps praise on ‘conventional wisdom’ which remains very influential, even if wrong.

Gale’s book reminds us that ‘creative accounting’, involving the transfer of debt and liabilities to state-owned enterprises or government-linked companies, has enabled the government to limit the growth of mainly ringgit-denominated federal government debt by rapidly expanding federal government-guaranteed ‘contingent liabilities’.

His defence and justification for GST ring quite hollow as his premise is that the middle class has been evading income tax, whereas it is mainly the rich who have successfully done so, whether legally or otherwise.

Although he has been writing on Malaysia for over three decades, he appears to have selective amnesia, only giving credit to the prime minister and his late father, whom no one would grudge, while ignoring other prime ministers and finance ministers, in line with the new official narrative.

Malaysians worse off?

Earlier, you acknowledged that Malaysian economic growth has continued, albeit at a lower rate, over the last two decades. Yet, you also argue that Malaysians may have become worse off in recent years. That sounds contradictory.

Jomo: Moderate economic growth has continued since the 1997-1998 financial crisis. More recently, this has been partly due to foreign financial inflows, helped by unconventional monetary policies in OECD economies.

Between 2012 and 2014, most people, especially low-income earners, became better off, thanks to the introduction of the minimum wage, continued ‘full employment’ and higher commodity prices.

Since then, commodity prices have fallen, unemployment has been rising (especially for youth), the GST was introduced, and consumer confidence has fallen lower than during the 1997-1998 or 2008-2009 financial crises.

However, consumer sentiment in Malaysia has been negative for some time according to CLSA and MIER (Malaysian Institute of Economic Research). Indeed, according to Nielsen, the international polling company, it has been poor since 2013, and is now the lowest in Southeast Asia.

Food prices have generally continued rising, as transport charges – for tolls, trains, etc. – have been increasing again, with floating petrol prices. Meanwhile, lower commodity prices and climate change have reduced many farm incomes.

Official unemployment has gone up from 2.9% in 2014 to 3.5% in 2016, still commendably low, although there are concerns about high youth unemployment, especially among the tertiary educated.

Retrenchments have been worst for services, casting doubt on future employment prospects as the authorities rely increasingly on services for growth and jobs. With unemployment low, but rising, wage growth has slowed after the initial introduction of the minimum wage, while real incomes have been hit by higher prices and taxes.

Wage depression

You seem to imply that Malaysian wages have been artificially lowered.

Jomo: Malaysians, in general, have higher incomes now than before. However, official numbers are misleading as we do not account for the massive presence and contribution of foreign labour, especially undocumented immigrant workers.

Their status has also served to depress wages for low-income Malaysian workers. Not surprisingly then, labour’s share of national income has gone down relatively.

This decline is not due to declining labour productivity, even if that may be the case. After all, higher labour productivity does not automatically raise workers’ incomes. Prevailing low wages retard technical change which would, in turn, raise productivity.

Thus, the unofficial low wage policy stands in the way of labour-saving innovation, such as mechanical harvesting, so necessary for development. We need a medium-term development strategy far less reliant on cheap foreign labour.

Consequently, wages and living conditions are too low, especially in agriculture. And even smallholder agriculture has been neglected by officialdom in Malaysia for some time, especially after Pak Lah’s (Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s) (photo) administration.

Fighting a jihad against middlemen was not only thinly disguised misinformed and misguided stunt intended to score ‘ethno-populist’ points, but also irrelevant to addressing contemporary challenges.

Shifting tax burden

How have recent tax reforms affected Malaysian households?

Jomo: Following the introduction of the GST in April 2015, tax revenue from households increased from RM42 billion in 2014 to RM67 billion in 2016, with GST more than doubling the contribution of indirect tax from RM17 billion to RM39 billion.

At the same time, income tax revenue has risen modestly from RM24 billion in 2014 to RM28 billion in 2016. On average, Malaysian households paid taxes of RM5,600 each, more than ever before.

Meanwhile, government subsidies and assistance have declined, falling from RM43 billion in 2013 to RM25 billion in 2016, with most food price subsidies removed between 2013 and 2016.

Inflation numbers

Official inflation numbers are low. Why does the public doubt official inflation numbers?

Jomo: There are many reasons why the public doubts official inflation numbers, but perhaps most importantly for the country’s open economy, the ringgit exchange rate dropped from RM3.2/USD to RM4.5/USD before recovering to RM4.2 recently.

People presume that a decline in the international value of the ringgit by about a quarter must surely have inflationary consequences.

The GST of 6% has been imposed since April 2015, directly affecting about half of household spending, with up to a fifth more indirectly affected. Again, this is expected to have affected the cost of living.

Price subsidies for sugar, rice, flour and cooking oil have been removed since 2013, raising prices by 14% to 31%. Meanwhile, transport – including fuel and toll – prices have risen on several fronts.

Hence, you can understand why people are skeptical.

Transformasi Nasional 2050 (TN50)

After announcing and then abandoning the New Economic Model, there is now much ado about an economic transformation agenda for 2050.

Jomo: The TN50 exercise has been broadly consultative, involving young people, which surely is a good thing. Unfortunately, as with BR1M, it has been used to mobilise political support for the regime before the forthcoming elections rather than open up a more inclusive debate about where the country is headed.

The conversation should be about where the country should go and how to get there. It is still unclear to what extent we are going beyond the usual feel-good, futuristic sounding clichés, but this should open up an important debate to give serious consideration to actually achieving the transformation.

The country is presently mired in a political crisis that has paralysed effective economic policymaking. Malaysia desperately needs a legitimate and consultative leadership to implement bold measures to take the country forward.

Many people in the country know what ails the economy, but we do not have the open discussion needed to really tackle the challenges the nation faces.

For example, a free and independent media will not only improve the quality of public discourse, but also the legitimacy and acceptability of resulting public policy.

Yesterday: Jomo in defence of honest, constructive criticism