COMMENT | “You know, Will, what we need to do is remove ‘race’ from our identity cards. We’ll start there. All Malaysians.”

It was like yesterday, but it was late 1985, the sun’s presence was strong, in a Sri Hartamas home, a child had been born, and my dear friend Rehman Rashid, as writers often do, was looking at a baby and seeing a story, the growing up, the future, a new country that lived up to its name.

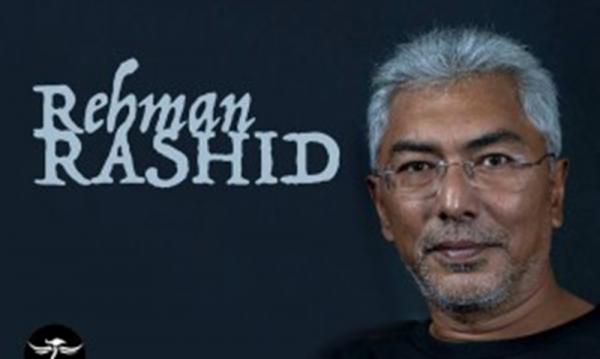

For those of you who don’t know Reh (Ray), and are only now beginning to read about him, know this: this prince of the land loved his country. It flowed through his veins and he was happiest to flow with it. He dropped off at many shores, but the river never let him be, and he always came home to Malaysia.

He just never saw it like the rest of us.

Ask him to write about the North-South Highway for his next Scorpion’s Tales, a column he had penned for years at The New Straits Times, and what does Reh do? He calculates the cost to a Malaysian padi farmer, if he had to drive from the southern-most town of that highway to its opposite end, and he measures that cost by everything else the poor farmer would have to forego in order to make that particular Malaysian journey.

That was his way of describing another Malaysian milestone in modernisation. We looked at highways, he looked at the toll.

That the article – which could easily have been seen as a critique of massive federal spending that, generations later, continues to be borne by taxpayers – even appeared in the NST speaks of how well a wordsmith can hide a killer punch in an establishment newspaper, and do well while he’s doing it.

Rehman didn’t just have a way with words, he could go to war with words. He often did in Scorpion’s Tales. Ultimately, every column was immensely readable, an icon for language, another unique take on Malaysia, in the Queen’s English no less, except in Rehman’s hands it was entirely his.

If each Friday edition of his Scorpion’s Tales was not being used at the time as a tool for teaching the English language in our schools, it should have been. His columns rarely had a dull moment, and even if you didn’t always need a dictionary handy, you had to pay attention. If you focused clearly enough, you’d see there is beauty in how words are strung together.

Lucky for him, many did. Before long, my kaki Reh was guest of honour or speaker at countless student events, many of which were in girls’ schools. Eagles in higher circles soon swooped in. The corporate and political world welcomed him.

If you knew him, you wouldn’t be surprised.

Big man, gentle hands

Rehman Rashid was unusually tall. Certainly for a Malaysian. He was tall enough to stoop, just that little bit, if he were talking to someone much shorter, almost in an act of kindness.

He was built. Just this side of ripped, because ripped can be vulgar, and you don’t want to get in his way. Long arms, like a loving gorilla, with gentle hands that belied the power hidden.

Add mastery of the written and spoken word and good looks to the mix, and you have the makings of a true Malaysian star, who had the good grace never to parade it.

And that voice.

On a particular day of living a bit dangerously, I cast Reh as the lead voice in a jingle I had been commissioned to compose and produce by an advertising agency, for Brand’s Essence of Chicken. It was the first time he had sung in a jingle.

Days after it played on RTM, I got a call from the editor of ‘Hotline’, a public-service section of The Malay Mail of old.

We knew each other personally, and he got straight to it: “Ay, who’s the singer on the English version of the ad?” he asked.

Someone who had seen and heard the jingle on TV had actually called the ad agency, to say he really liked the singer’s voice, assumed it was a foreigner, and wanted to know who it was.

So I told the friend on the phone it was Reh.

That it was a Malaysian singer behind the jingle became a Hotline story the next day.

Reh would of course have scolded his latest TV fan for equating “foreigner” with “must be better lah”, but such were the impressions he left.

Younger brother Rafique, an extraordinary musician and wordsmith himself, reflects on the presence of his sibling: “Your older brother is your first role model, hero, idol and dictator of your musical tastes.”

Some among Rehman’s friends, and I count myself in this number, as well as the movers and shakers who hold the keys to the kingdom, saw in this bumiputera a Malaysian who could eventually be groomed for politics, and the sky’s the limit.

But his very Malaysian-ness probably disqualified him. He just wasn’t enough of a particular type.

Rehman Rashid has moved on from his beloved country, never having fully recovered from a heart attack last January, leaving his mother and brother.

Malaysia needed Rehman Rashid, the nation needed a homegrown marine biologist to write A Malaysian Journey, Peninsula – A Story of Malaysia, all those sting-in-the-tale columns, the other books.

In the foreword to Peninsula, he began: “There are two ways to belong to a place: to be born there, and to die there.” It closes with: “Two-thirds of all Malaysians who ever lived are alive today, and they’re all our story.”

He lived a huge life, between being born and going. He looked at all of us and never stopped trying to put the pieces together, to tell ‘our story’ in a style all his own, with the eye of a scientist and the heart of a poet.

Some may say he was lucky. Gifted. But, know this: when Rehman Rashid meets his Maker, he will be able to say, I have used to the full the gifts You bestowed on me.

WILLIAM DE CRUZ was a friend of Rehman Rashid, and a colleague at The New Straits Times in the 1980s. They collaborated musically on several platforms.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.