COMMENT Assalamualaikum and good morning to all. It gives me great pleasure to be invited on behalf of the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) to this Conference on the National Security Council Act 2016 and its Implications on National Security and Human Rights.

The threat and reality of terrorism has grown exponentially and countries throughout the world have been struggling to develop effective responses to ensure their national security is protected. Such violent lethal activities have propelled nations to beef up their security and anti-terror laws. Malaysia too has followed suit, recognising that the rampant terrorism threatens the peace and harmony of the nation encapsulated in our constitution.

However in the process of effecting the nation’s response, the question that must be posed, whether those sweeping actions are in proportional response to the threat posed, or more would think in the process undermine underlying harmony and ethos as encapsulated in our constitution, affecting our individual and social liberties and freedom.

A significant proportion of Malaysians while accepting the need to be vigilant and defend our national security are questioning the enactment in recent years of various security laws such as The Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (Sosma), Prevention of Terrorism Act 2015 (Pota), and the National Security Council Act 2016 (NSC), amongst others. These security laws are among the critical issues of concern for Suhakam in light of its implications on human rights.

The National Security Council Bill 2015 went through the two Houses of Parliament and was gazetted into law on 7 June 2016 and came into force on Aug 1, 2016 by virtue of Article 66(4A) of the Federal Constitution without royal assent.

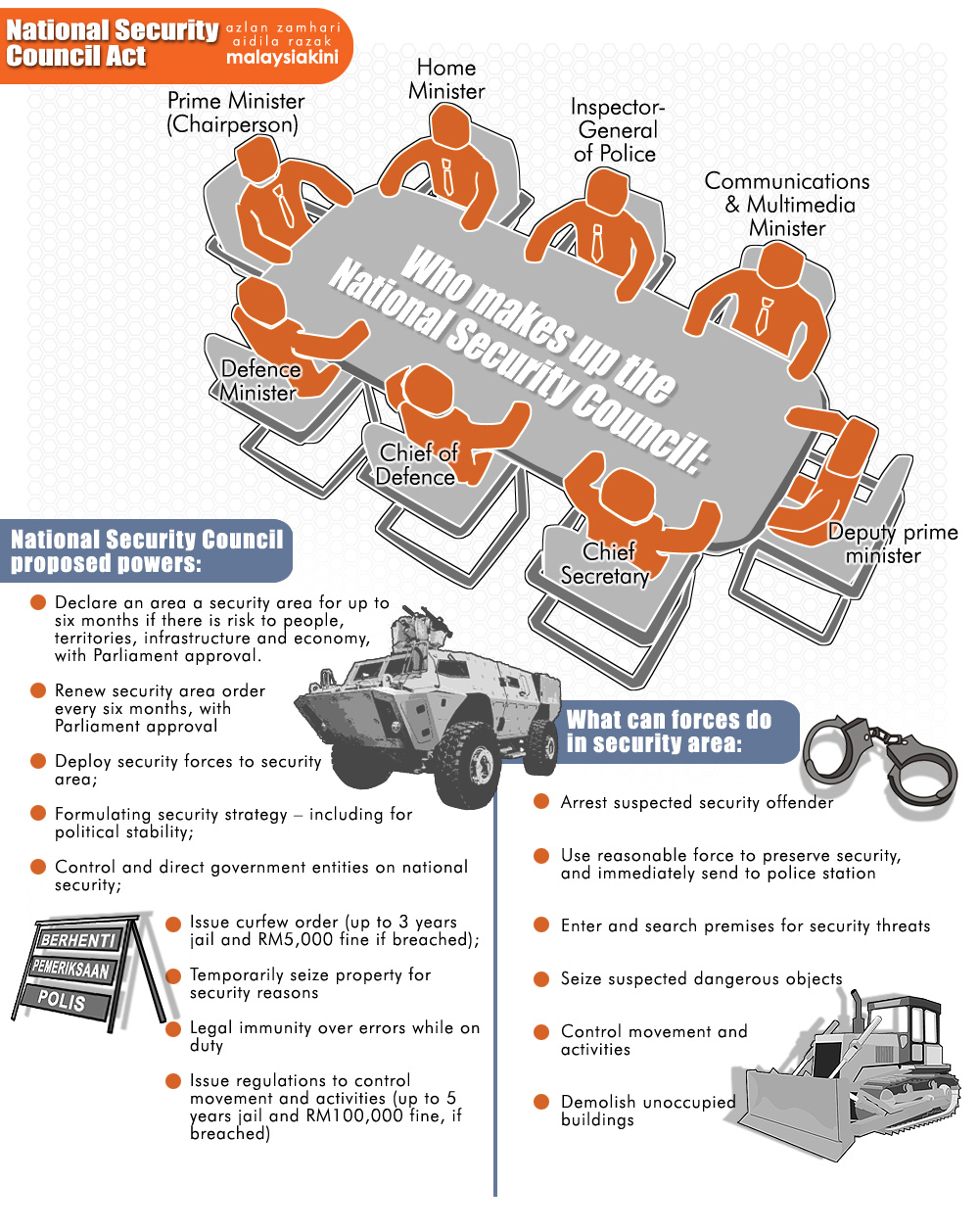

The National Security Council Act 2016, among others, allows the imposition of emergency-like conditions in security areas declared by a National Security Council led by the prime minister.

The exercise of maintaining stability, protecting the interest and security of the nation must be in tandem in promoting civil liberties and human rights. As a cardinal rule, it is the responsibility of the state as the guarantor of human rights, to ensure that peace is maintained and the rights of individuals are respected and protected even as the state needs to be vigilant to protect country and people from all manner of threats.

Granted this is easier said than done. There have been examples in the world where threats external or internal have resulted in the suppression of groups whose ideas are not in consonant with the state. Emergency areas, Military Operation Areas in those countries have trammelled rights in the name of security.

Closer to home, the internal conflict in Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, Indonesia (as an example), following a presidential decree declaring a ‘military emergency’ in the area and the imposition of martial law, led to the loss of thousands of lives, destruction of properties and suspension of fundamental rights.

In the said conflict, which has been well documented by human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, the imposition of martial law resulted in gross violations of human rights, such as unlawful killings, enforced disappearance, rape and torture.

The extreme example above does not apply to Malaysia and hopefully never will but against this backdrop and examining the substance of the NSC, the apprehensions of many Malaysians against the said Act are not unfounded as we all know that national security has long been one of the preferred tools by which many governments, even democratic ones, resort to controlling the free flow of information and ideas.

Without clear definitions or safeguards

Many provisions of the NSC are couched in fairly general terms without clear definitions or safeguards. Further, the unclear definition of security in the NSC may also be interpreted to suppress expression of thoughts, opinions or beliefs on public matters, including government policies.

Whilst certain rights may be limited to protect certain enumerated aims/purposes such as national security, public order, public health and morals and the rights and freedoms of others, those aims/purposes are not to be interpreted loosely. Of particular concern is that such unfettered powers granted under the NSC without proper checks and balances may threaten the state of human rights in the country.

Whilst recognising the need for security, Suhakam feels that the three branches of government, i.e. the executive, judiciary and legislature must play its respective roles as to complement each other to ensure that proper safeguards are in place to strike a balance between security and the liberties and freedoms guaranteed under the Federal Constitution of Malaysia.

Any denial of those liberties and freedoms must be proportionate, reasonable and in line with Malaysia’s obligations under the various international human rights treaties of which Malaysia is a party to.

There has been much debate over the declaration of a ‘security area’ under the NSC, in light of the absolute power given to the head of government to declare an area as a security area for a period of six months. Not only does the head of government have the power to declare a security area, he is also the chairperson of the NSC Council which in fact advices the latter on the declaration of a security area.

In addition, the head of government can renew the declaration for a further six months. Notwithstanding the consent of both Houses of Parliament to annul the declaration, this renewal can be done continuously without any limit. This implies that the NSC essentially gives unlimited power to the Head of Government, which raises concerns of accountability and impartiality on the part of the Executive.

It is imperative that the Judiciary and Legislature assert its roles as checks upon the Executive. Is there any way that suitable provisions can be added into the Act to manifest this serious concern by Malaysians?

No mechanism to review any direction

As there is no mechanism to review any direction or order made vide the provisions of the NSC, Suhakam advocates for the creation of a mechanism of review as has been emphasised in the report of the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism. The said report suggested that the review of security and anti-terrorism laws should include:

a) Annual governmental review of and reporting on the exercise of powers under counter-terrorism laws;

b) Annual independent review of the overall operations of counter terrorism laws; and

c) Periodic Parliamentary review.

The provisions of the NSC has various implications on human rights. For example, the preamble of the NSC does not explain satisfactorily or sufficiently the relevance and need to legislate this particular Act within the spirit of the Malaysian constitution. The nature and purpose of the NSC is important in order that to ensure that the goal it was enacted for is clear and does not diminish the spirit of our constitution.

The preamble in its current form is unclear and thus, may lead to an abuse of power as its objective and purpose is not clearly defined and there are no perimeters to limit the use of these powers.

Following that, the provision of the NSC provide powers to, amongst others, impose curfews, restrict movement, conduct warrantless searches, and take temporary possession of land or movable property. Whilst the security forces may require such powers during an emergency to protect the security of the nation, nonetheless, the Legislature must ensure that such powers do not encroach upon the individual’s and societies’ liberty.

Here, Malaysia has an obligation as a member of the United Nations to observe that pursuant to Article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (‘UDHR’), no one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

While Malaysia is not a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), it is nevertheless bound by customary international law, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and cannot comprehensively justify this broadly worded law as required for a state of emergency.

Suhakam urges the Legislature to play its role to proactively review the NSC with human rights in mind to ensure that relevant safeguards be inserted into the provisions of the NSC.

Judiciary should enure checks and balances

The Judiciary are in the best position to ensure there is proper checks and balances on the use of any legislation enacted by the Legislature.

As mentioned in the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, any decisions which limit human rights must be overseen by the Judiciary, so that they remain lawful, proportionate and effective, in order to ensure that the government is ultimately held responsible and accountable.

Suhakam regrets that the Judiciary’s role has not been specifically mentioned within the provisions of the NSC. For example, there is no mention of whether individuals affected by the operations in a security area have the right to seek judicial review for effective remedies against abuse to ensure that their rights are effectively safeguarded.

Suhakam is also aware that section 38 of the NSC provides for a blanket immunity against any action, suit, prosecution or any other proceedings brought, instituted or maintained in court against the Council, any committee, any member of the Council or committee, the Director of Operations, or any member of the security forces or personnel of other government entities in respect of any act, neglect or default done or omitted in good faith.

Such immunity undermines the role of the judiciary to afford affected individuals or groups the right to judicial review to ensure the due process are observed in the implementation of directions and orders under the NSC.

Suhakam asks whether the government have considered examples from other countries’ security provisions, which manifest a better balance and a sense of proportionality. We need to ensure that the three branches of the government complement each other to ensure a balance between national security and human rights.

At this juncture, Suhakam has been grateful for certain agencies of the government that have opened up relevant discussions with us. Suhakam would like to express its willingness to advise the NSC Council on matters of human rights and national security and the commission is open to any invitation to sit in the NSC Council’s meetings pursuant to section 10 of NSC, or alternatively a committee created pursuant to Section 12 of the said Act.

Our proposal is in line with the mandate and functions as contained in Suhakam’s founding Act. Whatever are the exigencies and compulsions under whatever circumstances, this country must honour and preserve our liberties and our democratic freedom.

Benjamin Franklin had said in 1755 that: “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety”.

This simple phrase reminds us that the philosophy espoused by both rights and security advocates has been played throughout the centuries countless times. Actors be it from the Executive, Legislative and certainly the participants of this conference must play their part to ensure that the balance do not tilt heavily towards the other end, thus ensuring the relationship between national security and human rights is always in tandem and in balance.

This is an important part of the Malaysian ethos.

Thank you.

This is the text of the keynote speech by Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) chairperson RAZALI ISMAIL during the Civil Society Conference on National Security in Kuala Lumpur on Aug 18.