MALAYSIANS KINI In the tumult that was the 1998 Reformasi movement, the PAS party organ Harakah was one of few alternative news sources available for those clamouring to know what was happening.

The paper was founded nearly a decade earlier in 1987, and the now 83-year old Ishak Surin was among those who started it all.

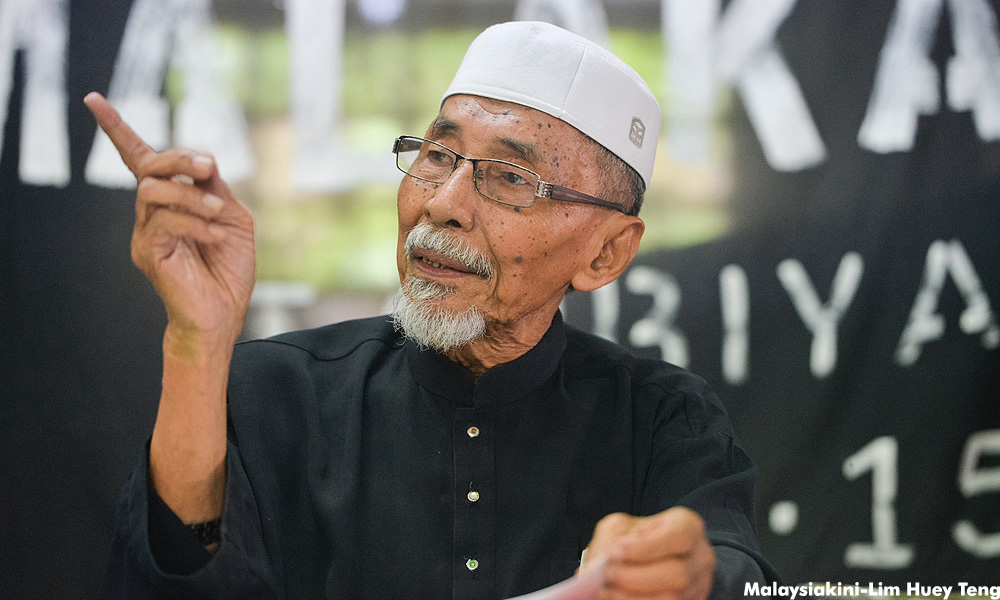

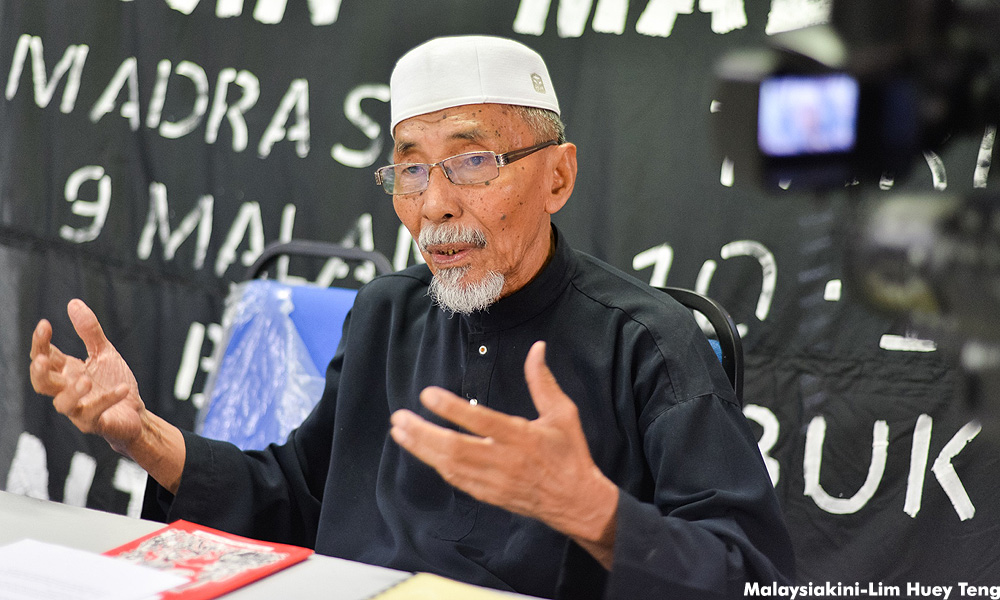

With an all-black robe draped over his slim frame, Ishak chuckled as he sat together with Malaysiakini and recounted the many twists and turns in getting the paper started.

With an all-black robe draped over his slim frame, Ishak chuckled as he sat together with Malaysiakini and recounted the many twists and turns in getting the paper started.

“If you look at the first edition of Harakah, it says it is printed by Tamil Osai,” he told two incredulous journalists present.

Hailing from Kampung Banda Dalam, Kuala Lumpur, in a quiet corner of the otherwise rapidly gentrifying Sentul area, Ishak was not short on all manner of interesting stories like these.

He was born in August 1934, and joined Parti Rakyat Malaysia (PRM) when it was formed in 1955, eventually becoming its assistant secretary-general in the mid-Sixties.

Fondly known as ‘Cikgu Ishak’, he is now the Amanah’s Batu Division chief, and was previously PAS’ Batu Division chief.

However he is best-known as a campaigner calling for the preservation of heritage sites in Kuala Lumpur - whether it is Jalan Sultan in the Chinatown area, Kampung Railway with its predominantly ethnic-Indian communities, or Kampung Banda Dalam that he calls home.

However he is best-known as a campaigner calling for the preservation of heritage sites in Kuala Lumpur - whether it is Jalan Sultan in the Chinatown area, Kampung Railway with its predominantly ethnic-Indian communities, or Kampung Banda Dalam that he calls home.

He was also Harakah’s manager during its early heydays.

It all started in the Dewan Rakyat, he said, when the then Home Minister Musa Hitam was questioned by a DAP lawmaker on the issue of printing permits.

At the time, PAS had been publishing booklets as a means to circumvent a ban on printing newspapers without a permit, with each booklet focusing on a single issue. It was selling like hotcakes.

“I think it was Lim Kit Siang. He asked why the Home Ministry wouldn't approve permits for political parties to publish newspapers.

“Musa Hitam (photo) was the home minister at the time. He challenged Lim and said, ‘Send it! If you don’t send the forms, how are we going to approve it?’

“Musa Hitam (photo) was the home minister at the time. He challenged Lim and said, ‘Send it! If you don’t send the forms, how are we going to approve it?’

“With a statement like that from Musa Hitam, we too went to get the forms, and asked to publish a newspaper […] Not long after, we got our permit.”

Political kryptonite

However, getting the permit turned out to be the easy part of Harakah’s founding. The hard part was convincing a printer to print a few pages of political kryptonite. Nobody seemed willing to take the job.

Fortunately, he said, help came in the form of a newsprint supplier named ‘Yap’ whom he had worked with when publishing PAS’ booklets, plus a little blackmailing.

“Wherever we went, nobody want to print Harakah. So I went to see Yap and told him that we have a permit. Then I told him, ‘You have to print this,’ and he said ‘Okay’ […]

“He went to an Indian newspaper called Tamil Osai, which bought newsprint from Yap. Yap threatened, ‘If you don’t print this, you aren’t getting any paper.’ So Tamil Osai printed it,” he laughed.

However, the unlikely alliance didn’t last as it quickly drew ire from Tamil Osai’s chairperson.

Ishak went back to Tamil Osai to ask for a reprint after the first edition of between 50,000 to 60,000 papers were sold out on its debut day, but was angrily refused.

After causing a stir however, Harakah managed to find a new home in another printing press in Balakong. This too was short-lived, after the printer refused to print an edition of Harakah that urged then Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad to resign.

Printed in Penang

Harakah then ended up with the Sulaiman Press in Penang.

However, Ishak said the Sulaiman Press was not the actual printer. Its machines were not even capable of printing a newspaper.

However, Ishak said the Sulaiman Press was not the actual printer. Its machines were not even capable of printing a newspaper.

Instead, Sulaiman Press merely lent its name to the printing operation in exchange for RM500 for each edition, and a letter of indemnity.

The actual printer did not want to have its name printed in Harakah, he said, as the company belonged to the younger brother of a state exco member.

“So every Tuesday or Wednesday, I would take a flight to Penang, and then back to Kuala Lumpur. Print; go home.

“Everything in Penang went well and I would go back and forth every week. I think this went on for about six months.

Then I found out that many printing presses in Kuala Lumpur (were interested),” he said.

Harakah had been doing business the ‘stupid’ way, Ishak explained. It would pay half of its dues in cash before printing, and paid the other half once the job was complete. This meant Harakah never owed any money to it printers.

“We buy, we pay; like buying pisang goreng. Once the paper is ready, we’d pay and go home. We don’t disturb anything. I think the big tycoons liked all of us ‘stupid’ people.

“We have heard of all sorts of things, but we knew nothing of it. We know that when you buy things, you’re supposed to cough out the money, and you take the goods away,” he said.

Perhaps lured by the prospect of getting a reliable paymaster, Ishak said the Kuala Lumpur printers that initially refused him, started to woo for Harakah’s business and tried to persuade him to save the weekly trip to Penang.

Perhaps lured by the prospect of getting a reliable paymaster, Ishak said the Kuala Lumpur printers that initially refused him, started to woo for Harakah’s business and tried to persuade him to save the weekly trip to Penang.

“So we were practically worshipping (the printing tycoons) back then but nobody dared to print. Everyone was afraid. But now everything is okay,” he quipped.

Eventually however, Ishak was sacked from his post after two years in Harakah, amid allegations of being a leftist, and of mismanagement.

He believed that the allegations emerged as result of jealousy within the party, as Harakah had managed to amass a small fortune of tens of thousands of ringgit at that time.

Still active in politics

Now, a great-grandfather of five, Ishak is still active in politics and intends to continue for as long as he is in good health.

He was a primary school teacher in a village in Sabak Bernam when he made his first foray into politics.

“There was no electricity, no water, and the roads were so small that a car couldn’t get through. I think that had an impact on me, to see the difficult life of the people there.

“There was no electricity, no water, and the roads were so small that a car couldn’t get through. I think that had an impact on me, to see the difficult life of the people there.

“So when Parti Rakyat was founded (in 1955), I joined straight away. I hated Umno at the time,” he said, adding that he had read leftist books while studying at the Tanjung Malim Teaching College.

“The zeitgeist of the time was independence. (The year) was 1954, 1955, 1956; there was a wave for independence. Everyone wanted independence.

“But do you know what I was angry about? People wanted independence, but Umno changed its tune to ‘Hidup Melayu (long live the Malays)’. […] No more independence.

“When ‘Hidup Melayu’, then what are the Chinese and the Indians supposed to do? Die? This is evil, so I resented it very much. Utmost evil,” he said, and the resentment has lasted to this day.

His political activities with PRM eventually landed him with a six-month detention under the Internal Security Act 1960, and then he was slapped with a RM2,000 fine under the Sedition Act 1948 in alternative to two year’s imprisonment.

He was sacked from his teaching position after attending a PRM meeting a few months after his release - in 1965 - although he continued to teach in private colleges and tuition classes.

He joined PAS in 1985 after a hiatus from politics, inspired by the Iranian revolution of 1979. He remained in the party until he joined PAS splinter party Amanah when it was formed last year.

KL's Cultural heritage

However, it is Kuala Lumpur’s cultural heritage that is closest to Ishak’s heart, and the rich history behind it.

“Take Kampung Railway for example,” he said, “The Indians there were brought in as railway workers and given a place there to stay. What wrong with preserving the place properly as a part of our heritage?

“The Chinese on Jalan Sultan; there are many historical places there. There was a place in Jalan Sultan that was a meeting point for independence fighters – to plan, to discuss, to oppose the colonists, and to win independence.

“It was the opera house (Yan Keng Benevolent Dramatic Association). It looks like an opera house, but behind it was where they met. I heard that even (Kuomintang leader) Dr Sun Yat-sen was there to discuss how to free our country from the colonists.

“With places like this, of course we must look after it. But these are the places that people want to tear apart. This is vile, very vile!” he said.

For the record, Sun was better known as a Chinese revolutionary figure more intent on establishing a republic to replace the Qing Dynasty in China, rather than oppose Western colonial rule.

His forays into Malaya and Singapore in the early 20th century was a bid to garner the support of the local Chinese diaspora for his revolution.

Ishak lamented that many would rather see more development in Kuala Lumpur than preserve its historical sites.

Although various campaigns had some success in stalling the onslaught of bulldozers, he feared that the developers were merely biding their time and would return once the older residents at the heritage sites had passed away.

“People don’t care, but I feel that this is important work that we should do. It is difficult and there is little support – people just want to build, build, and build,” he said.

This interview was conducted jointly conducted by Adrian Wong and Koh Jun Lin on June 15, 2016.

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

Previously featured:

Stroke victim revamps massage spas run by the blind

Discovering Pang Khee Teik - faith, sexuality, art and activism

Sex, religion and everything in between - Projek Dialog goes where few would

Gerakan Youth chief insists he’s no Twitter troll

Malaysian movie mania - Are viewers back for good?

Branded as 'deviant', Muslim scholar remains defiant

For Thasleem, life has indeed come a full circle

Poster girl for diversity? No thanks, says novelist Zen Cho

M’sian int’l hackathon champ shows computer games good for you

Pianist bears no grudge over concert cancellation due to Bersih 2

Facing possible jail time, Lena's main worry is dad finding out

This Malaysian youth has helped 10,000 Syrian families and counting