LETTER | State constitutions existed before 1957, and still exist and are in force. But the ruler's power to interfere in the administration of the state was curbed drastically when the Federal Constitution was enacted on Malaysia’s independence in 1957. From absolute rule to that delimited by the Federal Constitution.

Before then, the ruler presided at meetings of the executive council which administered the state. He was advised by the executive council, and by a Council of State presided by the menteri besar (MB). The MB was appointed by, and responsible to, the ruler. The ruler had the power to overrule the advice of the executive council and the Council of State. In short, he exercised absolute power.

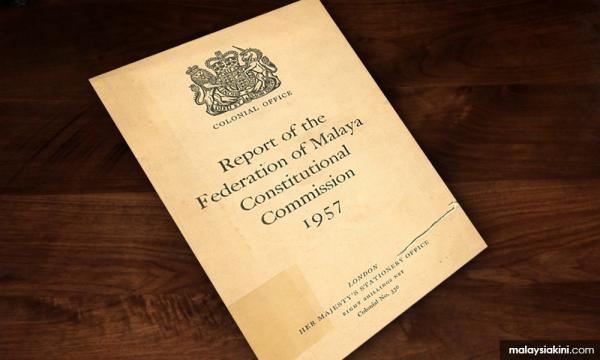

All this changed when the Federal Constitution was enacted. The Reid Commission, which crafted the constitution, altered this absolute power to that delimited by the constitution. Its remit was to safeguard “the position and prestige of Their Highnesses the Rulers as constitutional rulers of their respective states”.

Defined by the commission as “a ruler with limited powers, and the essential limitations are that the ruler should be bound to accept and act on the advice of the menteri besar or executive council and that the menteri besar or executive council should not hold office at the pleasure of the ruler or be ultimately responsible to him but should be responsible to a parliamentary assembly […]”

It would not be right, the commission declared, that the ruler as a constitutional sovereign should be involved in political matters. Henceforth the appointments to the state’s executive council “must lie in the hands of the menteri besar. Crucially, a new menteri besar must be free to appoint a new executive council in the same way as the prime minister appoints his ministers. In appointing or terminating the appointment of a member of the executive council the ruler must act on the advice of the menteri besar”. In all this, the ruler no longer had any decisive say.

The constitution thus reflects the ethos of parliamentary democracy. It provides that all states must include in their constitutions provisions which say that the ruler shall act on the advice of the executive council or any authorised member of the council and this advice must be followed.

If a state does not include this provision in its constitution, then Parliament can by law introduce this provision or remove any provision in the state constitution which is inconsistent with it.

It is in this context that we must read the prime minister’s statement that the State Constitutions were nullified. Essentially meaning that the absolute power of the rulers to run the administration of the state (as existed under the previous state constitutions) was abrogated. And that the Federal Constitution in this regard was the supreme law – subjecting all and sundry, no matter how high, to its commands.

The writer is a former law professor at Universiti Malaya.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.