This article on the Penang Transport Master Plan (PTMP) is in response to Dr Lim Mah Hui’s second letter to the editor ‘Lim Mah Hui’s reply to Roger Teoh on road-building frenzy’ published in Malaysiakini on June 2, 2016.

First and foremost, I would like to thank Malaysiakini for providing the platform for a healthy debate, with adequate coverage of contrasting views on the PTMP. It certainly raised awareness among Penangites on the topic, seeking to understand and discuss the most optimal transport solutions for the future benefit of Penang.

A holistic view of the PTMP

One of the objectives of the proposed road constructions in the PTMP is to create a bypass link around George Town. By doing so, road traffic users have the option to avoid going through the narrow roads of inner George Town. This diverts traffic flow away from the historic city centre, thereby allowing the limited road space to be allocated towards sustainable modes of transport.

For example, certain streets around the Unesco World Heritage Site of George Town will be pedestrianised in the future according to the PTMP plans. In the wider context, this will increase liveability, safety and street activities on the narrow alleys filled with street arts, also attracting more tourists.

In addition, the second phase of the PTMP will be to construct ground-level trams within this heritage area after the proposed highways are constructed and car traffic removed. With the new tram system linking other suburban areas into George Town, this will generate a positive knock-on effect on the road network on a wider area.

As quoted positively by Dr Lim, one tram with five carriages will take 200 cars off surrounding roads along the tram route. This is a no-brainer. Nevertheless, these highways proposed by the PTMP has to be constructed first before subsequent tram constructions in George Town can begin in order to keep disruptions to a minimum.

Moving on, the fear painted by Dr Lim in terms of “advocating the tearing down of houses and uprooting trees in the heritage city of George Town” is unfounded. According to the PTMP, there is no suggestion that the road alignment of the new highways will intrude into the Unesco World Heritage Site itself.

Despite being a councillor and part of the Penang Island City Council (MBPP), I am surprised to find out that Dr Lim is unaware of the main purpose of the PTMP, which is to divert traffic away from George Town. It is certainly not all doom-and-gloom for highway constructions in Penang Island. Personally, I would certainly join Dr Lim in protesting against the PTMP if the new roads require demolishing any highly sensitive cultural sites around George Town.

Accessibility vs connectivity

Next, it is true that Penang’s road network have good connectivity, which Dr Lim stated that all major areas and communities are well-connected. However, connectivity and accessibility are two different concepts. An area can be categorised to have a good connectivity but poor accessibility.

Accessibility is defined as the ease of a person in accessing a range of activity opportunities and services at other locations within a threshold generalised cost of travel (travel time and travel cost). To simplify this concept, take an example of a person commuting from Ayer Itam to Bayan Lepas for work.

At present day, it can take up to 1.5 hours to travel between the two areas during peak hours. If the Pan Island Link 1 link (Ayer Itam to Tun Dr Lim Chong Eu Expressway) proposed in the PTMP reduces travel time from 90 to 30 minutes for both buses and personal vehicles, accessibility is increased. Most Western European cities such as London adopts this accessibility formula for transport project evaluations and city-wide urban planning.

On the contrary, Dr Lim might also point out the idea of having segregated bus lanes on existing roads can equally reduce travel time, thereby increasing accessibility. However, this is not feasible as a reduction of existing road capacity in Penang has proven that traffic congestion will deteriorate to unacceptable levels.

For example, a reduction of road capacity in Penang along this example route (Ayer Itam-Bayan Lepas) can be adequately represented when a section of the Tun Dr Lim Chong Eu Expressway was closed on the August 17th, 2015 to build a multilevel bridge. This experience led to a three-hour long congestion in the morning peak, which the Penang state government rapidly reopened the section for general traffic.

Working towards a common goal

Despite of certain disagreements, there is also a consensus among Dr Lim and I which we both hope to see an increase in sustainable transport modal share in Penang. However, the difference is in our expectations on the duration of this transition period and its implementation timeline.

In an ideal world, the best solution is to reduce car dependence and use alternative modes of travel in the shortest period of time. However, it will be literally impossible and overly optimistic to expect a change in traveller behaviour to happen overnight.

A more socially and politically acceptable solution is a gradual shift towards modal alternatives instead of an instant radical change by reallocating existing road capacity towards priority bus lanes and ground-level trams, which will no doubt worsen congestion. This will almost certainly cause a public outcry.

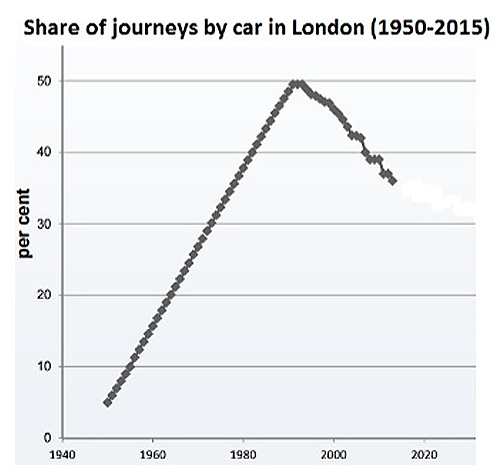

An example can be drawn from the city of London, which the graph above shows its percentage of car modal share from 1950 to 2015 (Metz, 2016). Although transport policy emphasis in London switched from ‘vehicle focus’ towards ‘personal mobility and accessibility focus’ during the early 1980s, car modal share in London continued to grow towards the mid-1990s (Jones, 2016).

An example can be drawn from the city of London, which the graph above shows its percentage of car modal share from 1950 to 2015 (Metz, 2016). Although transport policy emphasis in London switched from ‘vehicle focus’ towards ‘personal mobility and accessibility focus’ during the early 1980s, car modal share in London continued to grow towards the mid-1990s (Jones, 2016).

Nevertheless, it is also important to stress that London continued to build roads to unlock areas with poor accessibility after the early 1980s up until this very day. In fact, road traffic growth in London is still forecasted to grow by 1 percent annually from 2010 to 2040 (DfT, 2015). Although car modal share is decreasing, the absolute number of car traffic is still increasing. This shows that it is impossible to achieve negative road traffic growth even with significant public transport investments.

The difference after this transport ‘paradigm shift’ is that road construction has a lower priority over modal alternatives, but not entirely neglected. Again, similar circumstances is observed in the PTMP where the Penang state government plans to develop both road construction and public transport, instead of favouring one mode over another.

Nevertheless, the main point I am trying to highlight here is that it takes time for traveller attitude and behaviour to change. It took around 10 years after the ‘paradigm shift’ for car modal share in London to finally peak in the mid-1990s before reducing. Hence, is it too idealistic for Dr Lim to expect everyone to use public transport immediately by completely neglecting road constructions?

Another interesting example can also be drawn from Singapore, where despite highly restricting car use and achieving a 60 percent public transport modal share, the island republic is still building new highways. For example, the North-South Expressway in Singapore will be completed by 2020, connecting the East Coast Parkway with the northern parts of Singapore. It will be interesting to hear some comments from Dr Lim on this specific issue.

Finally, it is sadly true but not surprising that the Penang state has more roads on a per capita population basis than Singapore. The neglect on rail and public transport investments by the previous state government, as well as the automobile oriented policies by the federal government to promote the national car industry, unsurprisingly led to a higher roads per capita in Penang.

Balance is key

In conclusion, using the metaphor described by Dr Lim in his previous article, drugs used in small doses will provide medical applications and benefits. On both polarised ends, the deterrence of using drugs will not provide a step towards recovery, while an overdose causes addiction.

Therefore this is similar to road constructions, which has to be carefully controlled and planned. As Dr Lim rightly pointed out, an uncontrolled construction of roads not only fail to solve traffic congestion, it will also cause negative externalities such as air pollution and noise impacts.

However, the key point on this issue is to have a right balance. The alternative to automobile dependency is not a total elimination of personal vehicles, but rather having a multi-modal transport system meaning that travellers have diverse travel options to choose from. I believe this is well-addressed in the PTMP proposed by the Penang state government.

References

Department for Transport - UK Government (2015) Road Traffic Forecasts 2015. [Online] Available here.

Jones, P (2016) Long-term Trends in Urban Transport Policy Development in Advanced Western Cities - A model with wider application? Centre for Transport Studies, University College London.

Metz, D (2016) Peak Car - the Future of Travel. Centre for Transport Studies, University College London.

ROGER TEOH is a postgraduate student studying for an MSc in Transport Engineering at Imperial College London & University College London.