COMMENT | Thanks to voices from the public and within the political class, including that of Deputy Dewan Rakyat Speaker Azalina Othman Said, a hybrid sitting is now being studied after de facto Law Minister Takiyuddin Hassan and Dewan Rakyat Speaker Azhar Azizan Harun revised their opposition to the reopening of Parliament under the state of emergency.

Let’s be blunt. If social distancing is the reason for Parliament’s suspension, the challenge can be overcome in many ways: virtual, hybrid or even a physical session in two venues connected electronically. The obstacle is neither technological nor constitutional, but political.

It ultimately hinges on two questions:

- Will Parliament bring down the government?

- If the government needs to be kept in power, what is the necessary political settlement?

Palace's options

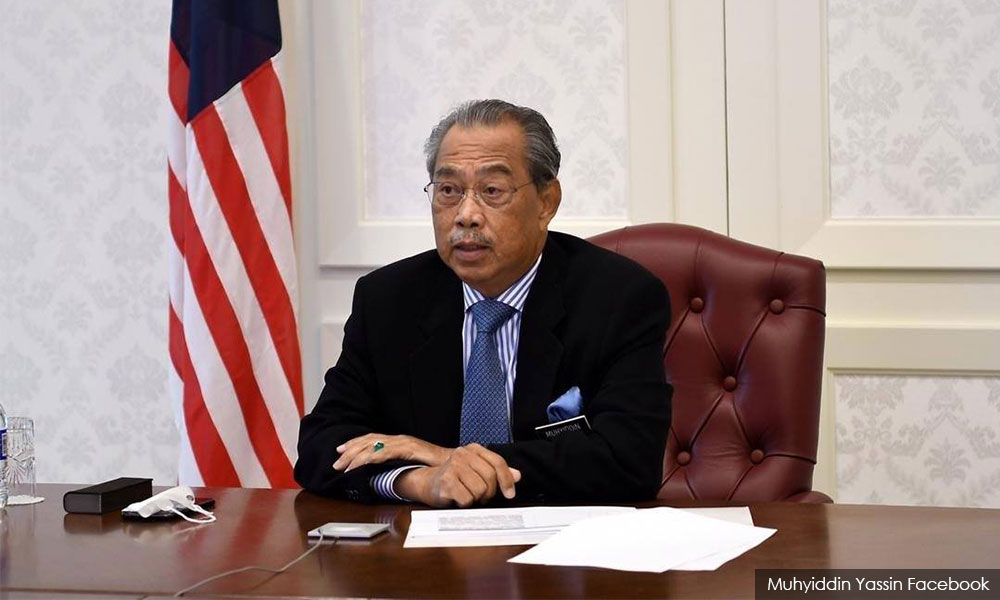

The emergency appears to be all about keeping a fragile government in power. If Parliament is reconvened, a vote of no-confidence can be passed, like how Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s party deputy Ahmad Faisal Azumu was dethroned as Perak menteri besar last December, with Umno and Pakatan Harapan joining forces.

If the presiding speaker or deputy speaker stands in the way, he or she can be removed too.

If a government is voted out, there are two possible outcomes in normal circumstances: a new election to produce a fresh Parliament, or a new government of a different combination, formed within the same Parliament.

The Covid-19 pandemic rules out the option of an election, which the king has rejected outright since last February. However, until Harapan and Umno – the two blocs that want Muhyiddin out – can agree on the next government’s formation, the ouster of Muhyiddin may trigger another round of MP-fishing, with no guarantee of a more functioning government than the current one.

This then leaves the palace with a few options on the menu:

(a) Partial opening of Parliament, allowing special select committees (SSCs) and all parties' parliamentary groups (APPGs) to operate and keep the ministries accountable;

(b) Full opening of Parliament without a political settlement with the risk of the government collapsing and a political stalemate;

(c) Full opening of Parliament with a reconstructed government with a stronger majority; and

(d) Full opening of Parliament with the same government, backed by a Confidence and Supply Agreement with the opposition.

Since the second option is least likely, I will first discuss the third and fourth options, which allow for a full opening. The first option with a partial opening will be discussed in another article.

Unity government

In theory, the second option of reconstructing the government can be achieved in more than one way. The simplest way is to reunite Umno and Bersatu, but that would be harder than reuniting Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie.

The next possibility is to bring Warisan’s eight seats into the government, which would raise the government’s majority to 121 (including Umno’s 36) versus the opposition’s 99 (including Umno’s Nazri Abdul Aziz and Ahmad Jazlan Yaakub).

Warisan may be interested in an offer of having a few key ministries in the federal government, Sabah government, or both. But the public is in no mood to stomach any more expansion of the federal frontbench to please job-hungry politicians, so any gain for Warisan would have to be a sacrifice from Umno or Bersatu.

Likewise, any state-level concession with Warisan having 21 state seats would certainly be at the expense of Umno (16 seats) or Bersatu (15 seats), further destabilising the Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) government.

Next is the idea of a "unity government" bringing in all or most parties, which effectively means adding Harapan. This is appealing to many, including well-intentioned intellectuals.

The 1974 formation of BN that brought into the government’s camp all but two parliamentary opposition parties - DAP and the now-defunct Sarawak National Party (SNAP) - is often the reference point.

That reference is very useful if we ask two questions: How long will this unity government last? If it is to be a permanent structure, how will parties in government compete against one another?

For BN, it was meant to be permanent, because its architect Abdul Razak Hussein wanted to eliminate “politicking”. This permanent characteristic caused both BN’s stability and corruption. But even that could not work for parties with overlapping electoral markets - after six years of cohabitation with Umno, PAS left bitterly after losing Kelantan.

Ironically, unless elections are abolished, any unity government will only bring about more disunity for one simple reason: Perikatan Nasional (PN), BN, Harapan, GPS, and GRS have overlapping electoral markets and will take on one another in the next election.

The crazy inter-ministry rivalries we see between ministers Azmin Ali, Ismail Sabri Yaakob and Khairy Jamaluddin will only be worse than now. And any cabinet reshuffle will cause more political fights!

If the Muhyiddin government cannot even deliver "Muslim unity", how can adding more parties that distrust each other produce "national unity"? If two Panadol pills cannot cure your diarrhoea, would half a dozen of Panadol pills do the work?

However, as many Malaysians have this insatiable fetish of unity, this idea will never die, even if it can never work. It will remain as a “what if” zombie for good people who do not understand politics.

Confidence and supply agreement

A Confidence and Supply Agreement (CSA) is a deal between government and opposition that keeps the government in power with the opposition agreeing to support the government, or at least abstain, on motions of no-confidence or budgets (technically termed, “supply bills”).

Like rental contracts and unlike marriages, CSAs are meant for a limited time, normally for a parliamentary term.

This is very common in countries like Denmark and post-1996 New Zealand, when governments are minority blocs or do not have a strong majority. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Adern’s first term (2017-2020) was a minority coalition government of her Labour Party and NZ First, backed by a CSA with the Greens.

Realistically, this is the only solution that may deliver political stability for Malaysia for the next 12 or 18 months or until Sept 16, 2023, when the next election must be called. This was offered by the opposition last August and October but snubbed by Muhyiddin and his senior ministers for fear of losing face.

For the sake of Malaysians' lives and livelihood, Muhyiddin should now go for a CSA that can buy him time to leave a positive legacy. As CSA does not cause cabinet reshuffles, he can please his ministers, upon whom his political survival depends.

For the CSA to effect ceasefire, it must come with two things:

- Fair treatment of opposition MPs and parties with key reforms of Parliament, Constituency Development Fund, Attorney General’s Chambers, MACC, etc;

- A promise of a free, fair and inclusive 15th general election (GE15) with a fixed date now, so that all parties can do their best preparation without feeling ambushed.

More than a political ceasefire, it will restore and enhance check and balance on the executive, paving ways for more coordinated and effective policies on the pandemic and economy, as well as the elimination of the “dua darjat” (dual-class) phenomenon in law enforcement, which ordinary Malaysians hate.

For such a CSA to be possible, both Harapan and Umno must also come to a consensus on what specific reforms they want from the government. Such consensus can be the basis of an alternative government if Muhyiddin cannot see his limited options.

WONG CHIN HUAT is an Essex-trained political scientist working on political institutions and group conflicts. Mindful of humans' self-interest motivation while pursuing a better world, he is a principled opportunist.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.